ICONS – Thomas Hoepker: Objective Realities

Hoepker was the defining photojournalist of the past century. He took arguably the most prescient photo of 9/11 still in the collective conscience and worked with a clarity that cut through some of the most complex political events of the 20th century. He didn’t see himself as an artist, but had what he believed was a higher duty to the world. How did he manage this?

Words Holly WycheA peasant kisses the feet of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, during a ceremony of distribution of land deeds. 1962

The ubiquity of images is perhaps the most significant change to how events are recorded and remembered in the past century. Images of crises are now so pervasive that desensitisation and resignation perhaps feel like the only feasible response to the suffering presented. As a result, venerated images of war and suffering are often lifted from their initial, objective context as record and given a status as ‘art’. Perhaps this makes them more palatable, replacing the nebulous, emotional charge these photos initially have with an easier-to-stomach aesthetic one. It’s easier to understand them as ‘iconic’ when they’re hung in a gallery and not seen in a newspaper, but it’s easy to forget just how inciting photos of the Vietnam War and deaths at the surrounding student protests initially were. But photos like these have time and time again moved people to action and changed history. Photojournalism thus falls far closer to a duty than an artform, and the photojournalist has a great responsibility in how they depict their subject and the impact that may have. Thomas Hoepker, one of the most renowned photojournalists of all time, is one of the most upstanding examples of this principle. Having photographed the divide between East and West Germany, famine in India and most famously, the apathy of bystanders during 9/11, Hoepker was painfully aware that the things he was capturing were real, visceral events with tangible consequences. He speaks of his work with great responsibility.

“As a photojournalist, I do my best not to influence the events I witness. If you started a conversation or asked permission, you would change any authentic situation in an instant.”

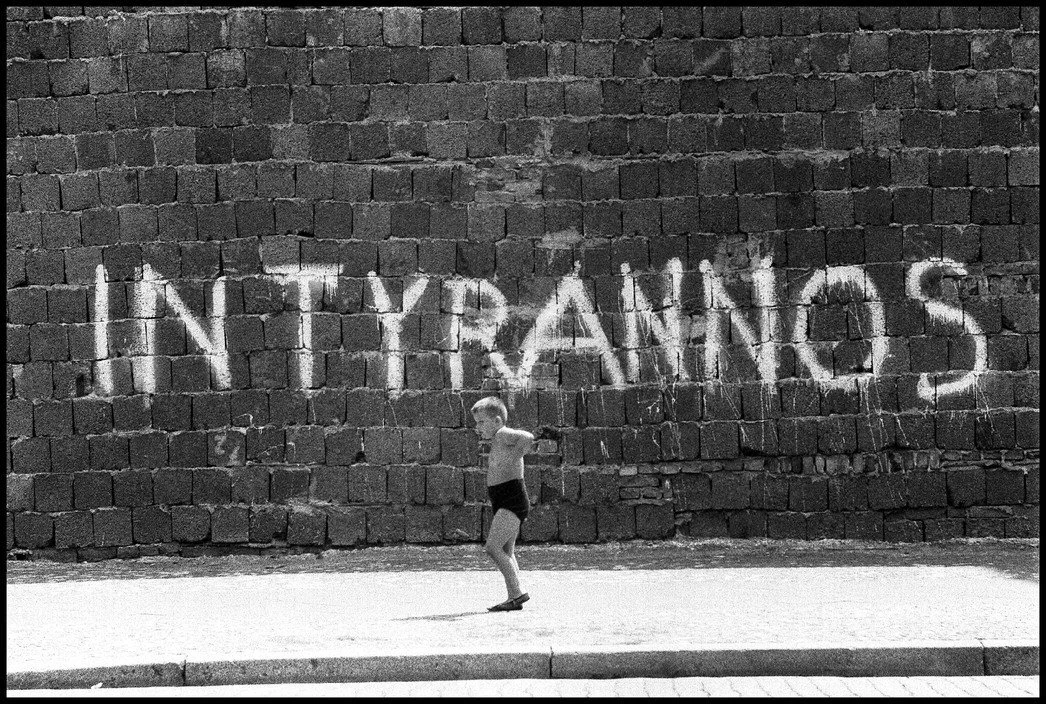

Italy 1956

Italy 1956

Hoepker’s early life was mired in the kind of conflict he would later cover. Born in 1936 in Germany, Hoepker’s family was relocated during the Second World War to Munich, where he started taking photos at 16 and developing them in his family's kitchen. His first success was found in trips to post-fascist Italy in his early 20s, taking biographical photos of other young adults attempting to rebuild their lives after the war. In this respect, a lot of his early work, even prior to official status as a photojournalist, is more biographical than aesthetic. While his composition is fantastic, it still feels like more of a record of life in Italy than an artistic perspective. His most famous photo of this era is ‘Love-birds in Rome’ and feels intimate even now, netting him two prizes in a young photographer’s competition in Cologne.

"I am not an artist. I am an image maker."

A child playing by the Berlin Wall. West-Berlin, Germany. 1963

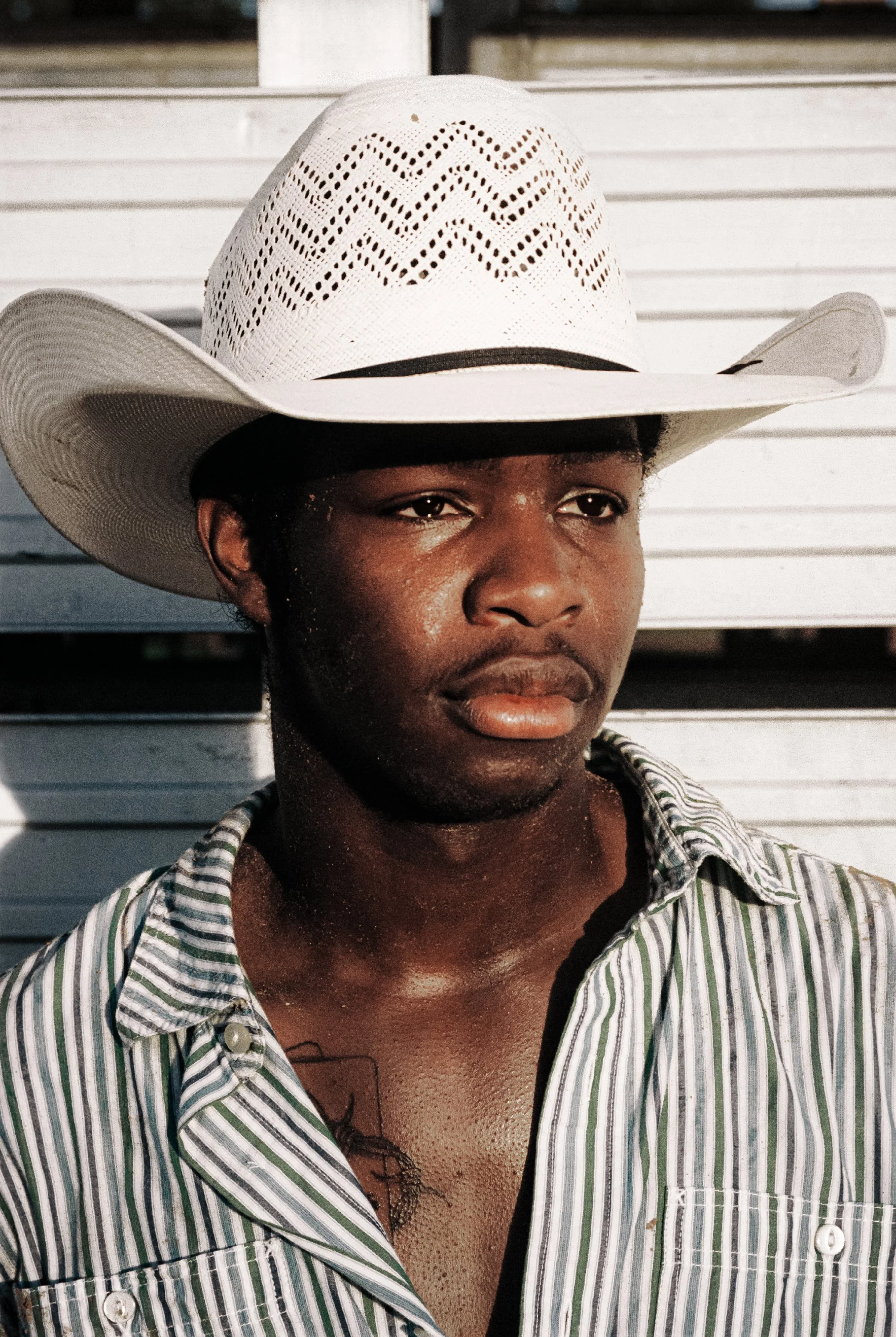

In fact, all of his work feels deeply, soberly grounded in reality. Hoepker allowed little romanticisation of the world, which was unsurprising given that his early photography followed war and famine. His work as the first West German photographer officially allowed to report from East Germany best shows this. Given the right to live in East Germany under a journalist-swapping agreement between the two nations, Hoepker rightly presumed his apartment would be bugged and worked deftly under heavily monitored conditions. Clarity is perhaps one of his greatest skills, and his work in East Germany was able to succeed precisely because it is so stark, and truths are shown so self-evident. He presented situations as he found them, able to see through any idealist or romanticised perspective forced on a given situation. This outlook preceded the limitations of working in a place as monitored as West Germany, and Hoepker had a similar critical contempt for 1960’s America, cutting through America’s post-war cultural boom with scalpel-like precision. He drove across America in a rented Oldsmobile Cutlass on a 3-month road trip, revealing disparity and inequality in what Germany at the time presumed was the land of milk and honey. He was later described as being “the only person who ever succeeded in making Florida [look] dark and gloomy”.

A beggar with amputated legs performs a headstand in front of a movie house, 1963.

Muhammad Ali, boxing world heavyweight champion, showing off his right fist, 1966.

“Time was always more important to me than being paid, because I wanted to familiarise myself with the topic. You have to know a lot, then you see things in a different light.”

US Marine Corps boot camp recruits are made to stand close to each other after having been shaved on their first day, 1970.

A guard and a child in a Bugs Bunny mask in the Forbidden City, 1984.

This absolute, objective perspective is one of the most important traits of a photojournalist. Resisting the urge to personify moments of hardship that most of the time are absurd and narratively unfulfilling is understandably challenging. Again, it’s more comforting to reify wars into grand stories than to understand them as disappointingly human and base failures. But if one is as transparent as Hoepker almost always was, a level of objectivity is afforded that can change the course of history. He worried this removed objectivity was a form of voyeurism, but maintaining the human at the core of his work almost always prevented this. This goes back to my point about responsibility and the refusal to reposition photojournalism as art. Hoepker was a stalwart defender of both of these things, and his values were deeply challenged in his most famous photo. That of an apparent apathy on the day of 9/11.

“Avoid all photo schools and courses. Most will give you lofty ideas and twist your mind in one direction. Find your own way to photography, nobody will ask you later if you have a diploma. Suppress any silly ambitions of becoming a great artist. Being a good photographer is difficult enough.”

Hoepker famously withheld this image from public release for 5 years, because it didn’t “feel right” and was almost “too pretty” to represent reality. His work is rarely voyeuristic or shocking, and this does feel different in some way. Not because of his intention but perhaps because the nature of the situation was so antithetical to how he liked to work. He worked slowly and with intention, learning as much as he could about a topic before photographing and reporting on it. Even outside of the context of 9/11, thoroughness like this is rarely possible anymore purely because story development now works on a timescale of hours rather than weeks. Regardless, even being released 5 years later the photo was still massively inciting. It’s remembered as one of the most prescient photos of the day, with a New York Times columnist remembering it as a representation of the country’s failure to learn: “What he caught was this: Traumatic as the attack on America was, 9/11 would recede quickly for many […] This is a country that likes to move on, and fast.”. The subjects of the photo later confronted Hoepker and said, “Had Hoepker walked 50 feet over to introduce himself he would have discovered a bunch of New Yorkers in the middle of an animated discussion about what had just happened.”.

The photo was international news and became one of the most conflicting representations of what 9/11 actually felt like for most Americans not near Ground Zero. Hoepker’s defining objectivity showed that 9/11 might not actually have been this conscience-strengthening rallying cry for Americans to come together, instead being a flash in the pan subsumed under other, greater acts of bloodletting. In this respect, Hoepker’s photo was one among millions of images of suffering produced that day. The difference with this one is that it showed that compassion isn’t necessarily the base reaction to said suffering. This is the power of photojournalism that Hoepker wielded and worried about. The capacity to change the popular narratives of massive wars and crises with a single pointed image is incredible, but deeply volatile. It must be approached with the care and objective humanity he always afforded his subjects. Photojournalism like his is not art, and that’s exactly why it’s more important than ever:

“The limit of photographic knowledge of the world is that, while it can goad conscience, it can, finally, never be ethical or political knowledge. The knowledge gained through still photographs will always be some kind of sentimentalism, whether cynical or humanist.”

Susan Sontag

The sun of the Japanese flag painted on a girl's forehead, 1977.

“Plenty of excellent pictures have already been taken of basic life situations – birth, love, mourning, death. There is a growing danger that we have already experienced and captured many situations too often.”

Times Square traffic. New York City, USA, 1983.

To find out more about his work, follow the official Instagram feed of Thomas Hoepker or visit his profile on the Magnum website