ICONS – Lee Miller

Lee Miller’s sprawling odyssey of a life is a profound achievement. She changed the world as a model, artist and journalist during World War II, leaving a deeper mark on all three disciplines than most people could hope to achieve in a lifetime. We take a look at her tour-de-force career.

Words Holly WycheOften writing these I try to find a central theme or word that encapsulates the artist’s life and approach to their work. Something that lets me even attempt to fit a whole person into a thousand words. Miller is the first artist I’m incapable of condensing in this way. She’s a throughline to many artists we’ve featured, being Man Ray’s lab partner and muse during the most fruitful period of experimentation either had, appearing alongside Margaret Bourke-White in the death throes of World War II, or helping invent commercial modelling as we know it. Miller is responsible for as much technical innovation as she is artistic and social revolution, and to focus on an individual part of her life would be a reductive reflection of just how much she achieved. Her life is easily mythologised, segmented into discrete narratives precisely because each is so rich and nuanced. Crediting her experience at war, her traumatic childhood, or exposure to other creatives as the reason for her brilliance are a reductive way of understanding a person who herself was profoundly insightful and changed the world around her from the moment she entered it. Miller is not the logical product of the forces exerted on her, formed from heat and pressure beyond her control. She was always an intense force in her own right, changing the world as much as it changed her.

“I saw the Sinai Mountains Sunday dawn – the most incredible burst of surrealist painting imagined… Max Ernst in Turner’s colour… I was filled with awe and relief – and irreality.”

Miller stumbled into the New York modelling scene after being pulled out of the way of a speeding car by media magnate Condé Nast himself in the early 1920s. After Nast sensed her potential, she became famous almost overnight, gaining acclaim for her androgynous features and capacity to inhabit any character in front of the camera. Even then, Miller had a deep curiosity for photography, studying under photographers as she modelled for them. Despite her impact as the first ever commercial model, she still identified as a Pictorialist, believing in photography’s capacity for artistic expression over anything else.

Edward Steichens Portrait of Miller – 1928

Her time as a model was more tumultuous than is commonly understood, however. In the public eye, she profoundly impacted women’s gender expression as this androgyne figure responsible for the popularisation of short haircuts. Her early work was even reprinted in World War II to convince female factory workers to cut their hair short as a stopgap solution for headlice epidemics. Behind the scenes, however, Miller felt trapped. Sketches were later found in her journals, drawn by Miller in the early 1930s, depicting a woman pinned in place on stage by daggers. She was pulled from place to place as a New York socialite and reduced to a clotheshorse. This mirrored the worst elements of her early childhood, forced to model nude by her father from the age of 8. The context of her childhood, if acknowledged at all, is often glibly mythologised, pitching her constant reinvention as a response to this traumatic experience. I understand the desire to reposition suffering like this as something not entirely senseless, but these events do not need to fit a satisfying narrative. It left Miller unmoored in this early period of her life, unsure if she ‘ever was meant to fit together’. Miller eloped to Paris in the late 1920s to pursue her Pictorialist approach to photography that the newly formed standards of commercial modelling wouldn’t allow for. Ironically, her face was partly used to create these standards. Given a letter of recommendation by a mentor, Miller crossed the world to pursue a figure as popular and revitalising as her. Her future professional and romantic partner, Man Ray.

“I told him boldly I was his new student. He said he didn't take students and anyway, he was leaving Paris for his holiday. I said, “I know, I'm going with you” – and I did.”

During this bohemian period in pre-World War II Paris, the pair engaged in this constant, iterative artistic explosion. New approaches to photography and types of chemical manipulation produced in this time have become fundamental building blocks to the whole discipline of photography. The extent of the work produced in this time is still mindboggling. It’s one of the few times you can look at an adolescent artistic medium and pinpoint not just the exact moment, but the exact room that it reached adulthood in. Ray is sometimes solely credited with the innovation their time together brought about, with Miller being understood as more of a muse than an active participant in their experimentation. This is entirely untrue. Miller herself was responsible for the discovery of ‘solarisation’, the process of re-exposing a negative to light during processing to cause the tones in a photograph to partly reverse. This creates a halo of light around the subject, and was commonly used by both Miller and Ray for years following.

Corsetry, Solarised, London – 1942

“Some of them are pictures I saw in my imagination, just as I would a painting, and I assembled the material for them.”

The more morbid aspects of surrealism are also wrongly attributed to Ray, and Miller herself had a penchant for transgression. Nudes where Miller’s body is completely divorced from her personhood, instead appearing as abstracted flesh, are the result of Miller’s eye. The most striking example of this is photos of a mastectomy Miller recorded while documenting surgeries in a Paris hospital. There’s a blunt curiosity in these photos that demonstrates how Miller was fascinated with the taboo or things out of reach for the average person. She and Man Ray made for excellent bedfellows for precisely this reason, and despite their romance not lasting, they stayed profoundly important to one another. Miller was one of the first called when Ray passed nearly 40 years later. Ray’s second wife reportedly said to Miller. ‘He is still warm. I will kiss him for you.’

Man Ray: “My darling Lee, I shall try to be everything you want me to be toward you, because I realise it is the only way to keep you. You are so young and beautiful and free, and I hate myself for trying to cramp that in you.”

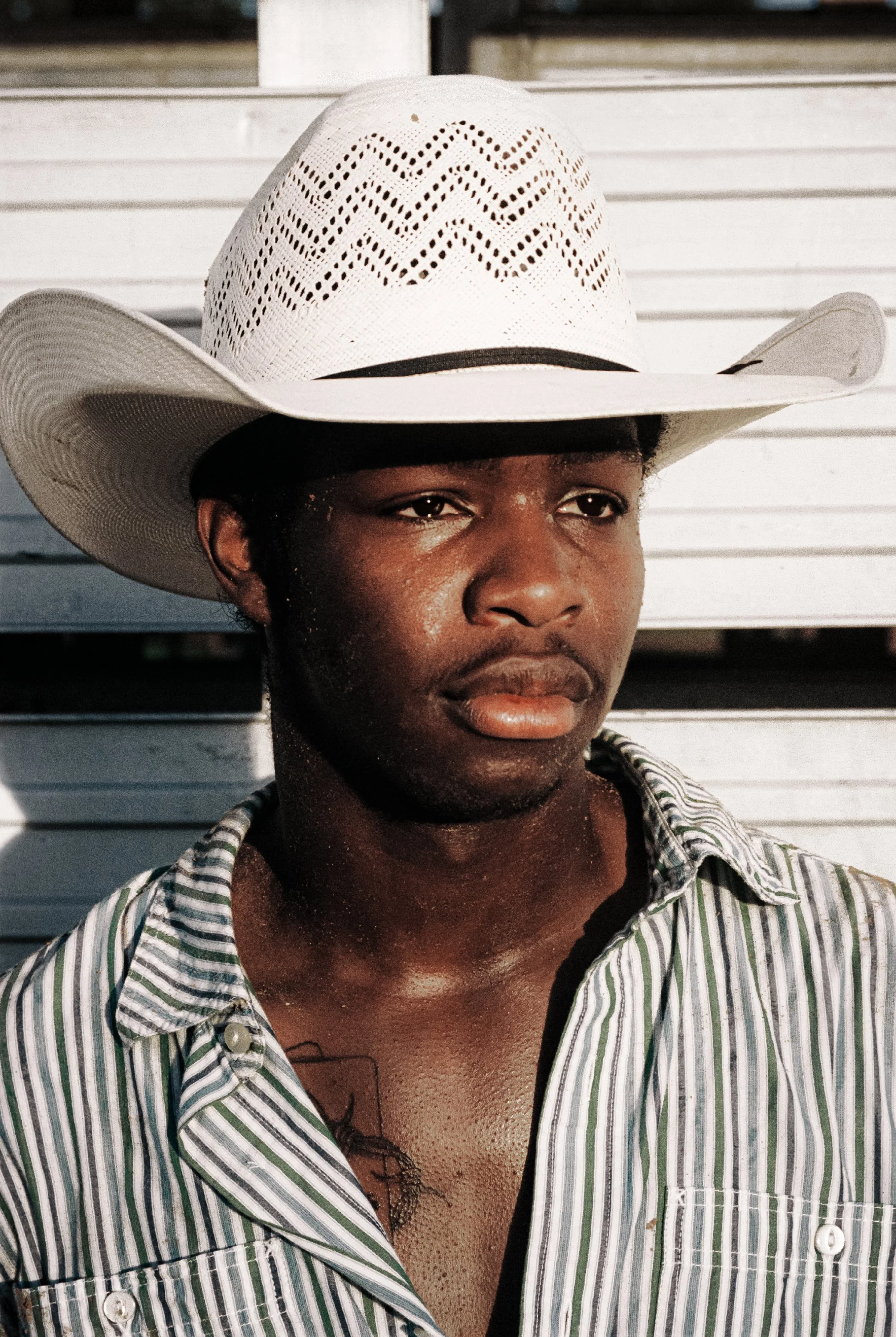

David E. Scherman dressed for war – 1942

Following her time with Ray, Miller turned from the abstract to the deeply sobering, instigated by the arrival of World War II. The bohemian life Miller and her contemporaries flourished in had been all but destroyed, and driven by her trademark temerity and deep opposition to Nazi politics, Miller captured some of the worst atrocities to ever take place as a photojournalist for Vogue. The contradiction between Miller’s public identity and her new work left her torn between two worlds. She was seen as too frivolous for the frontlines and too gritty for the art world, with a lot of her work produced on the holocaust not being published by Vogue because of just how horrific it was. Despite this, she marched on, staying in Germany until about 6 months after the war ended. This is the core of Miller’s character. She was constantly fearless, facing adversity head-on and fighting for artistic and personal freedom from the moment she stepped out onto the New York street. In each of these turns, away from modelling and towards surrealism, from the studio to the frontlines, Miller vehemently fought for herself. She was profoundly rebellious and the extent of her impact on the world can’t be reduced to any one of these three careers. The culmination of this attitude came in Miller’s seminal photo in Hitler’s apartment the day he killed himself. Miller and her Jewish assistant, David E. Scherman, take turns cleaning themselves in Hitler’s bathtub. Miller was absolutely fearless.

“It was a matter of getting out on a damn limb and sawing it off behind you.”

Lee Miller and her assistant David E. Sherman in Hitler’s bathtub