ICONS – Irving Penn: Still Life and its Pleasures

Penn’s Still Life work, one subsection of an eminent career in photography and the arts, speaks to the power of a genre rarely viewed as gripping. A staple of the arts world for generations, and the throughline through all of Penn’s work, Still Life will always endure. How might Penn’s work allow us to see it for what it is?

Words Holly WycheBouillabaisse (Barcelona, 1948)

What is the point of a Still Life?

Like any painting, what should we get out of it? In the case of Still Life, our inclination could be to look at its verisimilitude, the painter’s capacity to create a lifelike representation of the subject. The subject is finite and inanimate, and its apparent ‘realness’ is often the first thing we might notice. There is visible craftsmanship in this practice that is certainly eye catching, but beyond this it might be a little unclear what exactly an arrangement of objects is trying to tell us. Perhaps because of this, Still Life colloquially has a reputation as potentially being boring compared to other genres. Derisive comments of paintings as ‘just bowls of fruit’ is often the first thing people actually think when seeing the most traditional staples of the genre. This isn’t necessarily a surface level opinion either. The French academy established a literal hierarchy for painted genres in the 17th century in which Still Life was ranked the bottom, due to its lack of human subject matter and thus perceived depth. It’s in this gap between reality and art’s representation of reality where the ‘interesting thing’ a lot of art has to say often lives, and an art form that could be focused on closing this gap might seem self-defeating. Or at the least, open to criticisms of dullness. How much can one say in simply attempting to record reality and its objects?

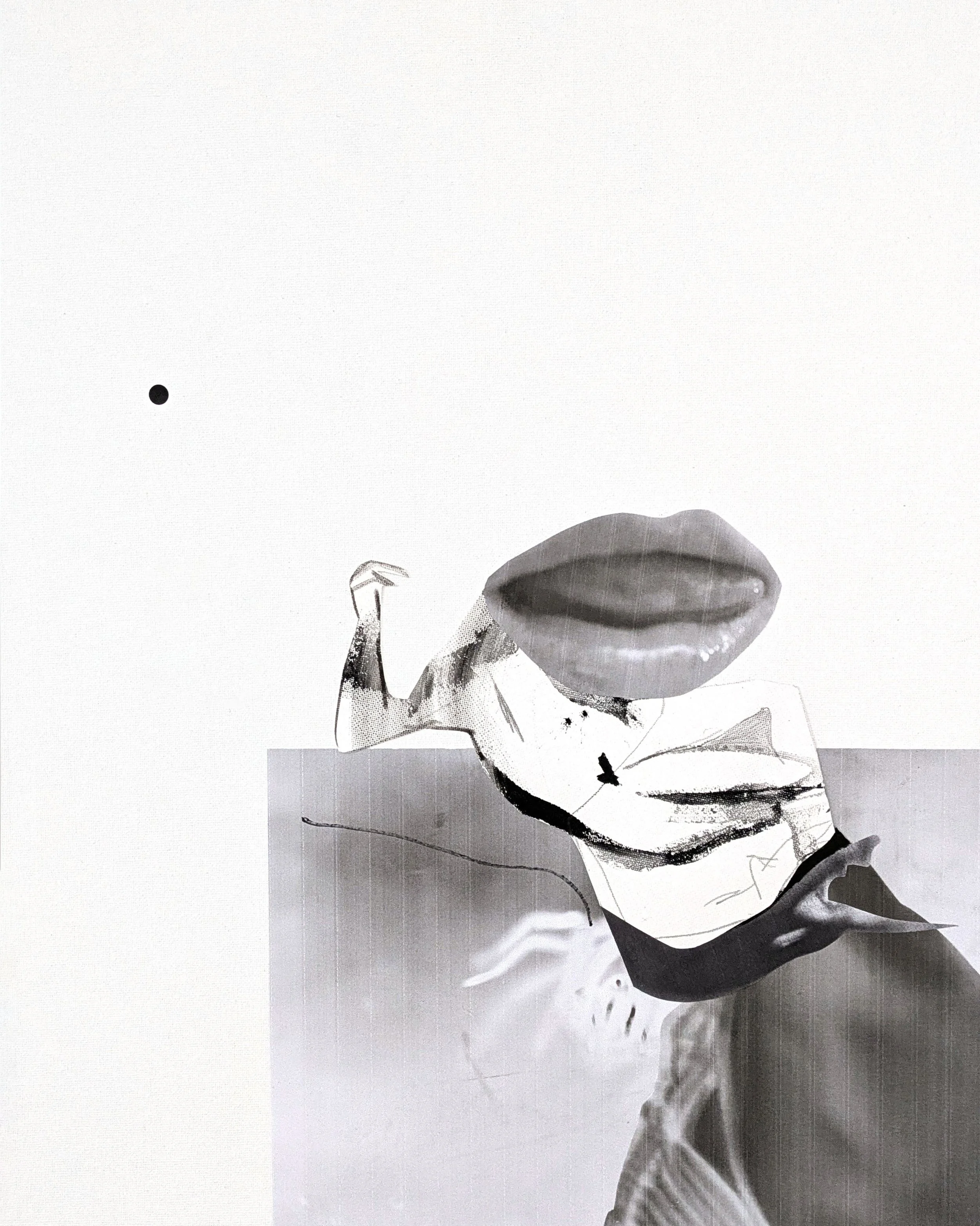

Bug in Ear (A), New York, 1959

“A good photograph is one that communicates a fact, touches the heart, leaves the viewer a changed person for having seen it. It is, in a word, effective.”

Red-Lacquered Lid, New York, 1994

Now, this is a narrow-minded reading. But it’s a common sentiment that brings us to Irving Penn, a generational talent whose work serves as the antithesis to the pessimism laid out above. If documentation really is the primary, narrow, focus of painting a Still Life, then what could possibly be the point of photographing one?

Born in 1917, Penn was a classically trained artist before he was a photographer, and this perspective is impossible to miss in his work. He was primarily a fashion photographer by trade, working for Vogue and Harper's Bazaar. While this is where most of his notable commercial success lies, it’s also a box that constrained him. By 1950, after a decade in the industry editors often felt that his photos were “too severe” for Vogue. “They [burned] on the page.” He had an intensity that this is indicative of, previously destroying all his paintings produced in a year stint in South America purely because they were disappointing. He even avoided looking at his commercial work at all because "they hurt too much." Penn had both the regiment and rigour of a classical painter at a time when photography was primarily a communicative endeavour. An act of recording reality, instead of necessarily saying anything yourself.

“The printed page seems to have come to something of a dead end for all of us.”

Ripe Cheese, New York, 1992

This was the ideology that Penn always clashed with. He desperately pruned away anything outside of the frame that encroached on his intentional vision. Chance and improvisation were not something Penn valued about the medium, and what John Berger termed as the “weak intentionality” of photography was always something he was trying to counteract. He would create impromptu studio spaces out of garages or barns wherever he could make them, requiring the almost scientific sterility of a laboratory to experiment. Penn resented the sentiment that the photographer made only a “single constitutive choice”, that of the moment they photograph, and instead positioned everything with such precise intention that his commitment to a loose medium like photography almost becomes baffling.

Theatre Accident, New York, 1947

The Empty Plate, New York, 1947

“I feed on art more than I ever do on photographs. I can admire photography, but I wouldn’t go to it out of hunger.”

Penn’s rigour is why Still Life as a genre began to underpin and seep into the rest of his photography. It wasn’t his most commercially successful work, but its principles and intentional, confined borders suited Penn’s artistic neuroses. He dutifully arranged objects within his sterile frame, and his composition both resembled and diverted from classical painted Still Life regularly. Penn’s classical training is absolutely on display in how much he chooses to engage with the canon in each piece. Regardless, what we immediately notice when looking at these pieces is that above all else, they’re just deeply gripping. His capacity to breathe life into his subject matter isn’t our first question like it might be with a painting, as the realness of his subject isn’t necessarily in question. Instead, what the medium of photography instead lets us see first is narrative and temporality.

Salvador Dalí (1 of 3), New York, 1947

“In the studio, too, I like it to be in no way grand. Nor do I feel grand, because I’m full of doubts still about the ability to get the picture I’m going to take.”

Game nights dusted with cigarette ash, half-drunk liqueur glasses and cups of tea introduce a temporality to his work we’ve seemingly stumbled in on. Penn’s object selection is certainly poppier than a lot of classical Still Life and helps us think this relational way. We can easily position ourselves in a waning poker night or stumbling on a handbag spilled open on the pavement, and it’s the temporariness of these objects that shunts us into his world. Warm meals and the suggestion of temperature introduce a precise window in which we’re viewing these objects, but other classical objects like fruit still give us a limited window in which we’re viewing these pieces. This is a moment in time, and we temporarily exist beside it.

This is what Still Life is trying to communicate with its bowls of fruit and ‘Memento Mori’s. Mortality and temporariness linger and leaves beauty in its place. The focus on death as a purely symbolic representation in Still Life came initially from the Protestant Church and its grievances with idolatry. The worry of religious paintings of saints being a form of sacrilege was high, so fruit and its rot became shorthand to admonish the viewer about their relationship to earthly pleasures and their fleeting nature while not showing its proponents directly. Even in more abstract Still Life this Protestant hang up persists and rot rings out. Francis Bacon’s ‘Chicken’ or Picasso’s Still Life featured these motifs for example. But Penn seems to answer in his work with a perhaps more hopeful version of ‘Vanitas’. The bohemian life that Penn shows us, full of seafood and cigarettes certainly might seem a little base, and even a bit grotesque when shown to us as bluntly as he does, but there is a romance in the pointlessness of it all. This is the sentiment that carries through Penn’s work, and where his base in Still Life allows us to appreciate the world in its most grounded way. Even his portraits of people in different profession seem to be a little starry eyed. Deep sea divers look like alien bug men, with milkmen and bakers looking almost cartoonishly committed to their trade. Life is short and impermanent; we must take stock of the things around us. Still Life might seem dull, and a photography of it might seem even more so on principle, but Penn’s capacity to present us earthly delights show us its merit. It isn’t life or how apparent it might be that is the focus of Still Life, it’s the pleasures it contains. This is Still Life’s point.

Two Liqueurs, New York, 1951