The Anthropocene Illusion

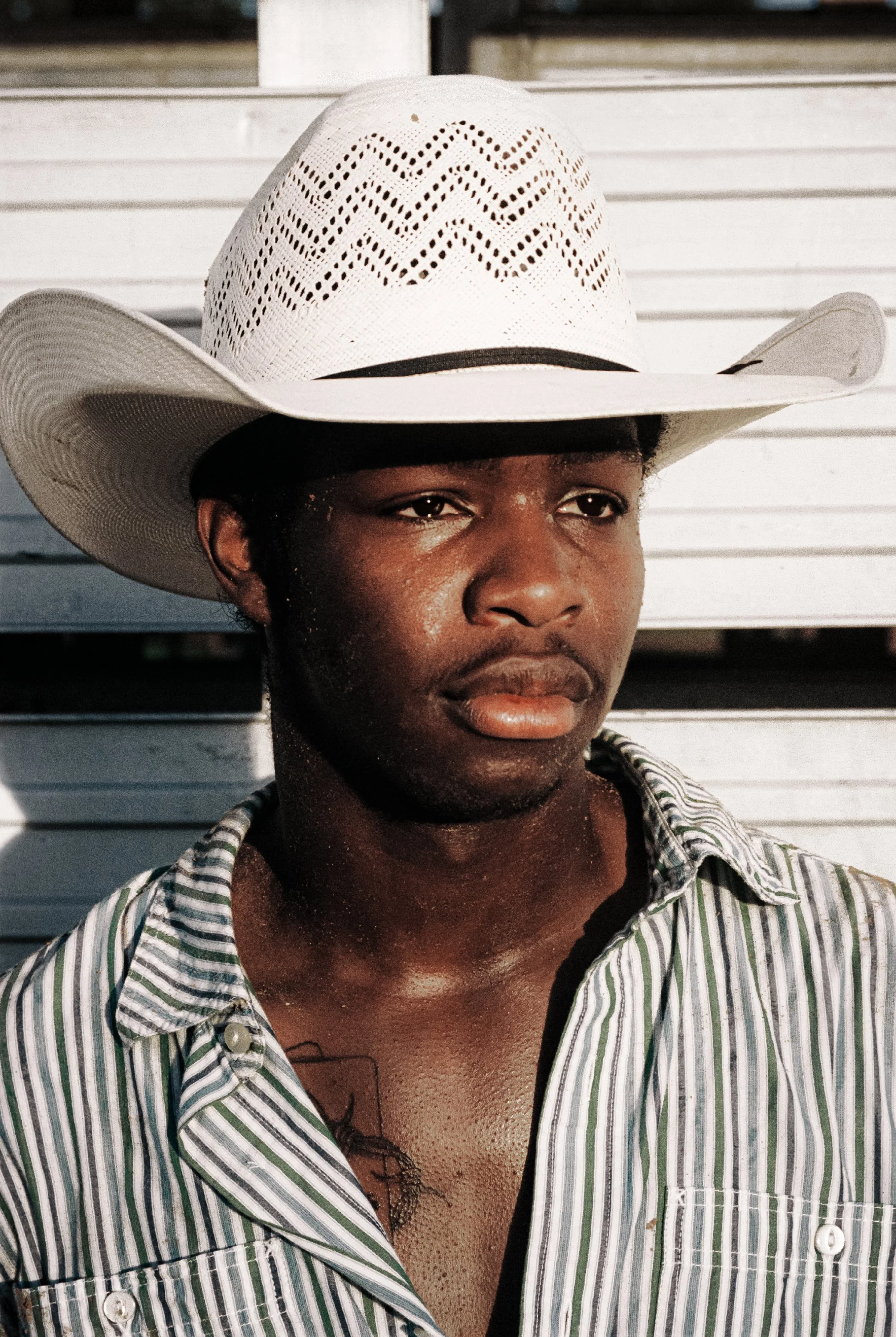

British photographer Zed Nelson has just been awarded ‘Photographer of the Year’ for his series ‘The Anthropocene Illusion’. His work focuses beyond the destructive human impact on the natural world, examining the sterile environments humans have built to satiate our craving for natural spaces. We spoke exclusively to Zed about what inspired him, his approach and how the project developed over the course of six years.

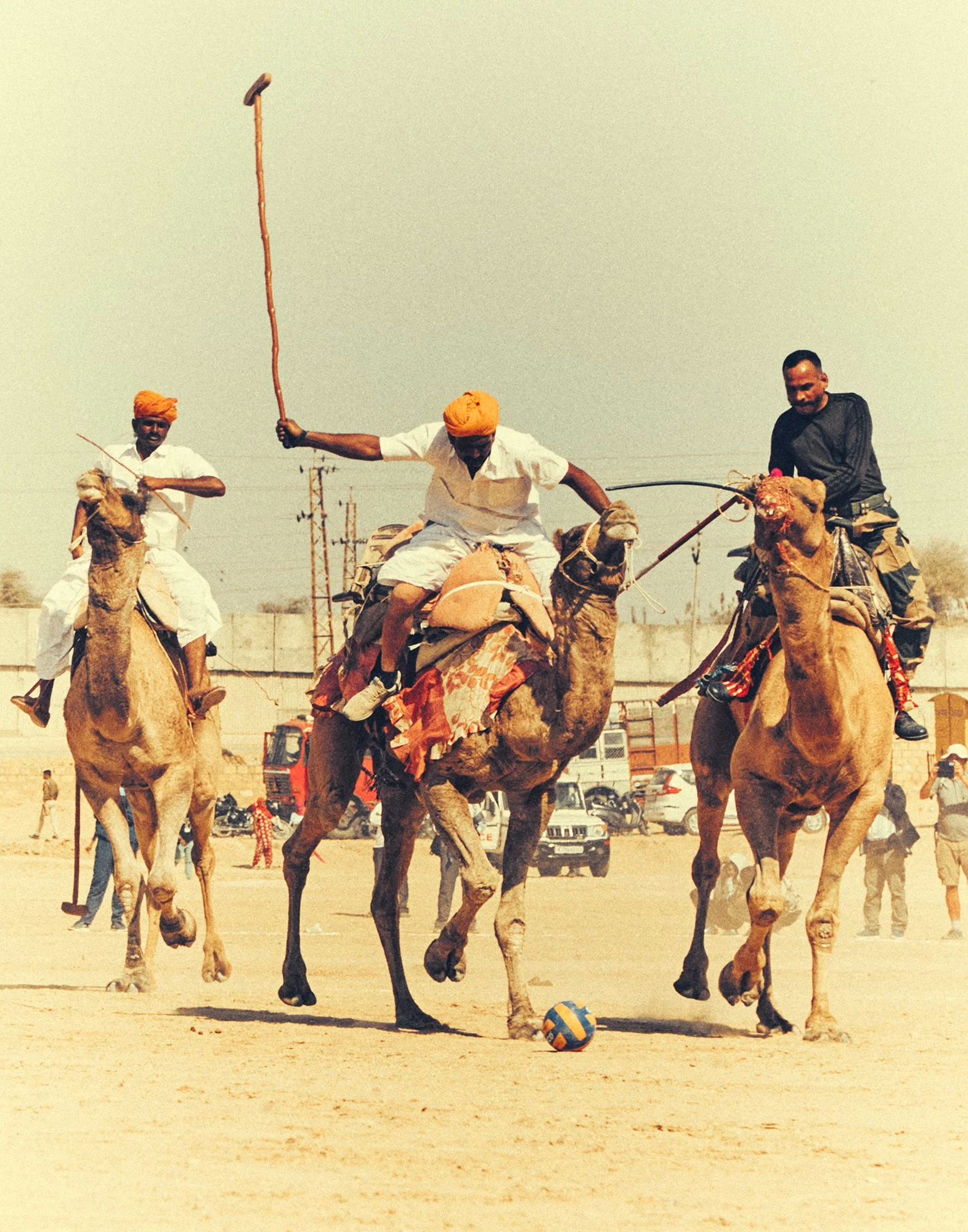

Words Holly Wyche Photography Zed Nelson Sony World Photographer of the Year, Zed Nelson, confronts environments he bluntly describes as “hermetically sealed” and “divorced from the natural world”. His subjects are facsimiles of the natural world designed to replicate environments we are rapidly destroying. Human impacts are so beyond anything we’ve seen in tens of millions of years that scientists have proposed we’ve entered a new epoch, ‘The Anthropocene’, or the age of the human, defined by our effect on the climate and physical world. We have irreparably altered the world, and Zed reveals the zoos, ski slopes and artificial resorts we’ve created in response.

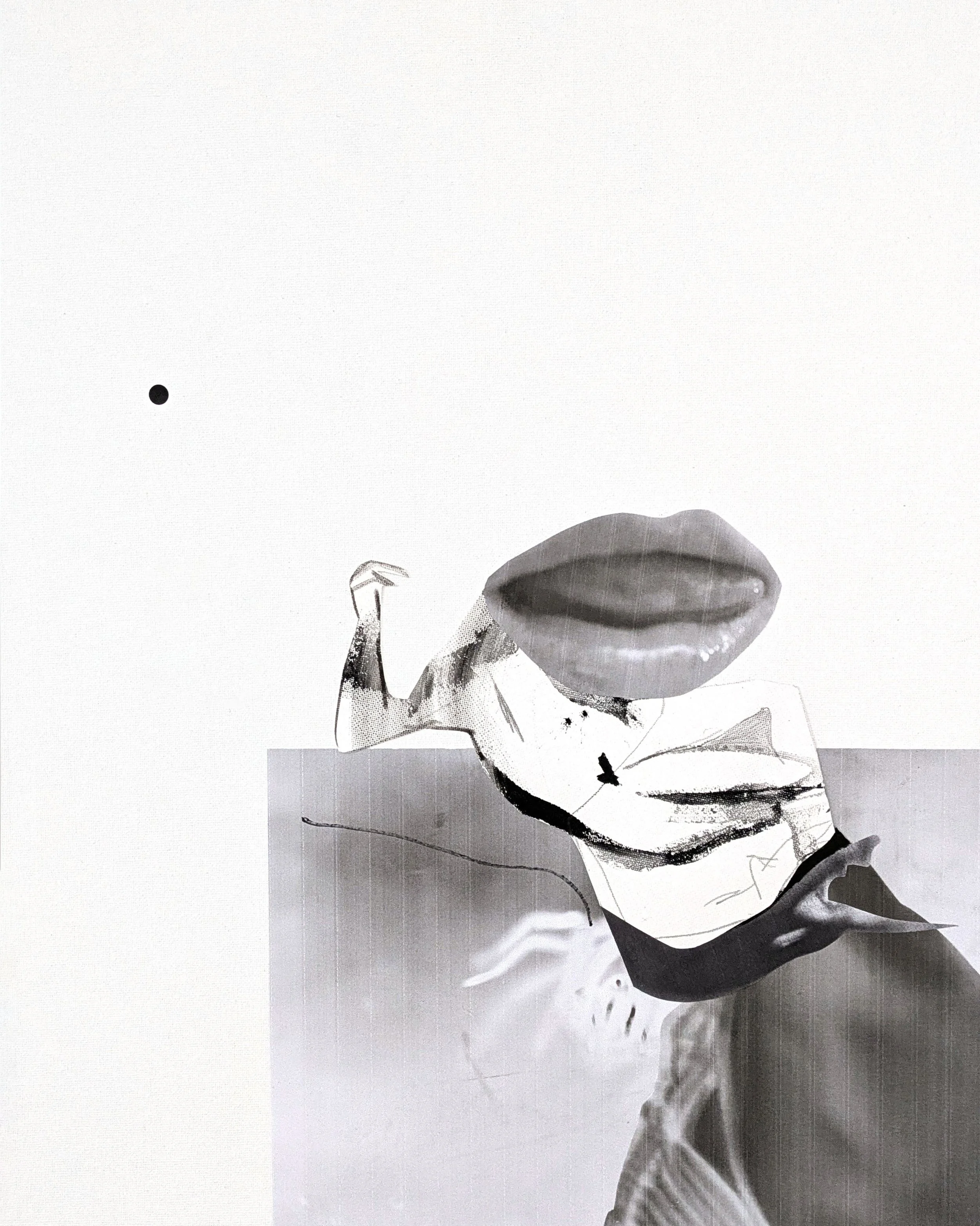

The project is about how we humans have divorced ourselves from the natural world. Zed explains, “Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, something has occurred where humans have divorced themselves from nature more and more. So what I've focused on is how at this precise moment in our evolutionary arc, we have retreated and created more and more artificial, choreographed or curated versions of nature. This project argues it’s done either to obscure what we're really doing, even from ourselves, or to create a way to get this connection with nature that we crave. We have destroyed much of the natural world, and yet we still have this kind of innate craving for a connection to it. I was really interested in trying to approach it in a way that was different from the typical environmental story, where you see images of melting ice caps, and rubbish strewn wastelands.”

“We have retreated and created more and more artificial, choreographed or curated versions of nature.”

You worked on this project over the course of six years. Presumably your goals for what you were trying to achieve must have changed over that time as research changed?

Funnily enough, I began researching it even earlier than six years ago. It could have even been like 10 years ago. My feeling then was, ‘why is nobody talking about the environment, really talking about it?’ Obviously, there were some things happening, but I mean on a very general, popular level. And then and certain things did change during that time, like Extinction Rebellion as a protest group happened. They put a lot of things on the public agenda, and even lockdown also had an effect, I think people became more appreciative of nature. And then awful populist leaders started getting elected, which reversed all the good that seemed to have happened. All the hope that we felt after lockdown, and all the kind of radical feelings generated by Extinction Rebellion, all that then got quickly undone in the way by the terrible leaders suddenly start taking power. But is that itself a symptom of the Anthropocene illusion? Are we so committed to this illusion that we will even elect people who will sell us lies and fabrications so we cannot face anything, take any responsibility? So, there have been changes during the project, but it hasn't changed the feelings fundamentally of what the project's about.

“When you're in a place that's in this sort of commodified, sanitised version of nature, it's remarkable how few surprises there are. It's like being dead in a way.”

You speak a lot about the fact that in these artificial spaces, the ones you recorded, that there are no surprises. Are there any of those spaces that particularly stuck with you after completing the project?

Well, that's the funny thing. They don't stick with you. In those hermetically sealed places, you come away without any strong memories. When you're in a place that's in this sort of commodified, sanitised version of nature, it's remarkable how few surprises there are. It's like being dead in a way. You just glide through it. There are no markers of anything.

My interest isn't so much to criticise any one of these places. But seeing the pictures, seeing the realities of the way we treat other animals, to create illusions for ourselves and so-called natural experiences. Some of those stay with me. They haunt me. But the more generic experiences and theme parks, they don't leave any memories really.

As you said a lot of your work is shot over the better part of a decade. How do you decide when a project like that is complete when the subject has continued developing and the scope of the topic is always changing? You spoke about your work on American gun culture going from being a citizen issue of gang violence to one of the advertising industry for example.

It's a good question and there's no easy answer. With ‘Gun Nation’, I had to stop because I started getting argumentative with the people I was meeting, and that was the end of it. In order to make that work, I had to just be very open and not express my opinions and I just found myself increasingly frustrated. And in the end, there's an urgency to sort of get it out into the world. At the end of ‘Gun Nation’ the Columbine High School shooting happened, so I included that as the last chapter of the book. It felt like, “Okay, I'm done. I'm also frustrated. I'm getting argumentative. My opinions are spilling out. I'm no longer just an observer. I now need to start commenting on it.” I mean the work itself is a commentary, but that needs to be in the world to have any value as a comment.

The topics that you cover are, a lot of the time, incredibly tense. Racial segregation in South Africa, the effects of civil war in South Sudan, what moves you to cover conflict?

When I began as a sort of documentary photographer, I was interested in hyper-political, charged situations. At the beginning, I felt like “If you go and photograph a war, then you shine a light on the injustices of it, and you help spark conversation and dialogue, you save the world through photography.” And then I had a real reality check, and realised that it wasn't that simple, and that these situations that you would go to were very complex and nuanced and contradictory. It's about money and economics and power and racial groups and all sorts of things, but newspapers didn't want to know about the contradictions. They just wanted a picture of a starving child or a boy soldier with bullets wrapped all around him. So, I realised that those images themselves were kind of clichés and they weren't very useful. And in fact, they were probably very unhelpful. I was struggling to tell stories in a more nuanced way, but the people I was working for didn't want to hear that complexity.

“There's a kind of innate craving in all of us to be listened to and to have other people find us interesting, or to get our views across. If you give people a platform to do that, they often do.”

What I always find interesting, particularly for documentary photographers is getting access. How do you manage getting access in areas which are dangerous, difficult to access, and where people don't feel like you want to exploit them?

It really changes. I'm always surprised, but the things that you expect to be the hardest things turn out to be the easiest things. I remember for ‘Love Me’ I wanted to photograph vaginal surgery, because there was a whole industry in LA of designer vaginas. I thought that's going to be a tough one for me, a male, to go into that world and photograph. But it was weirdly easy. And yet, when I wanted to photograph breast implants in a factory on a conveyor belt, it took me two years of writing to companies who just wouldn't let me into their factories, and I thought that was going to be easy. However, in more extreme situations, like going to a war in Afghanistan, sometimes you have to find a way of aligning yourself with an aid agency who are working in that area, who can offer you some kind of logistical support and advice.

The other thing is that humans really like people to be interested in us. Sometimes you think that something will be really hard, but there's a kind of innate craving in all of us to be listened to and to have other people find us interesting, or to get our views across. If you give people a platform to do that, they often do. Like doing the gun project in America, I went to a gun convention in Dallas. I walked around with a 35 mm camera, and I started taking pictures, and people abused me like they literally told me to fuck off to my face. I had press credentials, but all the people there were incredibly hostile. There's also something about the psychology of photography. So on the third day I took in a big medium format film camera and a tripod. I set up a backdrop with lights, with a couple of umbrellas, so it literally looked like a portrait studio, and everything changed. People actually started queuing up to be photographed. I learned something about the psychology of the way you present yourself to people.

My final question to you. Are there any new projects that you've been working on in the background, or is there anything that we should be looking forward to?

Sometimes at the end of a project, you know, I'm sick of it, and I want to get away from it. After ‘Love Me’, all I wanted was anything other than that. I didn't want to go to another beauty convention. I didn't want to sit with another plastic surgeon who was looking at my nose and thinking I needed a nose job. I just wanted to be in a different world. But with this, I'm still in this world, and it's, it's a very active story in a way. So, I imagine I'll still kind of be working on smaller stories.

About Zed

Zed Nelson is a London-based documentary photographer and filmmaker, known for long-term projects that explore contemporary society. He has published three books, Gun Nation, Love Me and A Portrait of Hackney, and has been recognised by numerous photography awards, including the Visa d’Or (France), First Prize in the World Press Photo Competition (Netherlands), and the Alfred Eisenstaedt Award (USA).

His work has been published and exhibited worldwide, with solo shows in London, Stockholm and New York. His work has been exhibited at Tate Britain, ICA and the National Portrait Gallery, and is included in the permanent collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

To see more of Zed’s work, visit his website or follow him on Instagram