Iwona Blazwick: The sublime and the intimate

Iwona Blazwick OBE, former director of the Whitechapel Gallery and creator of the Turbine Hall commissions, returns to the gallery space after years of monumental desert curation. She’s begun conceptualising a new exhibition that’s much more intimate, focusing on photography’s capacity to reveal private, profound parts of the photographer’s life without even showing them.

Text Holly Wyche Photography Christa HolkaCuration as an artform itself is under-examined. As the position of ‘curator’ is a powerful one, often held by those who’ve been in the art world for decades, there’s a sense it requires an unknowable, almost spiritual relationship to art that one can only gain from a lifetime of work. As such, any opportunity to actually understand what it takes to create exhibitions is invaluable. Blazwick has moved through almost every medium art has to offer, curating over 100 exhibitions at the Whitechapel Gallery, the Tate Modern, and London’s ICA as an independent curator. Her sense for how to exactly understand the effect of an exhibition or a specific piece is one of the most potent out there. She’s recently returned to the gallery space to dissect how photography can reveal deep-seated truths about the photographer, and how that sets photography apart from every other medium. We speak to her about how she arrived at this conclusion, and what it takes to turn this sense into an exhibition:

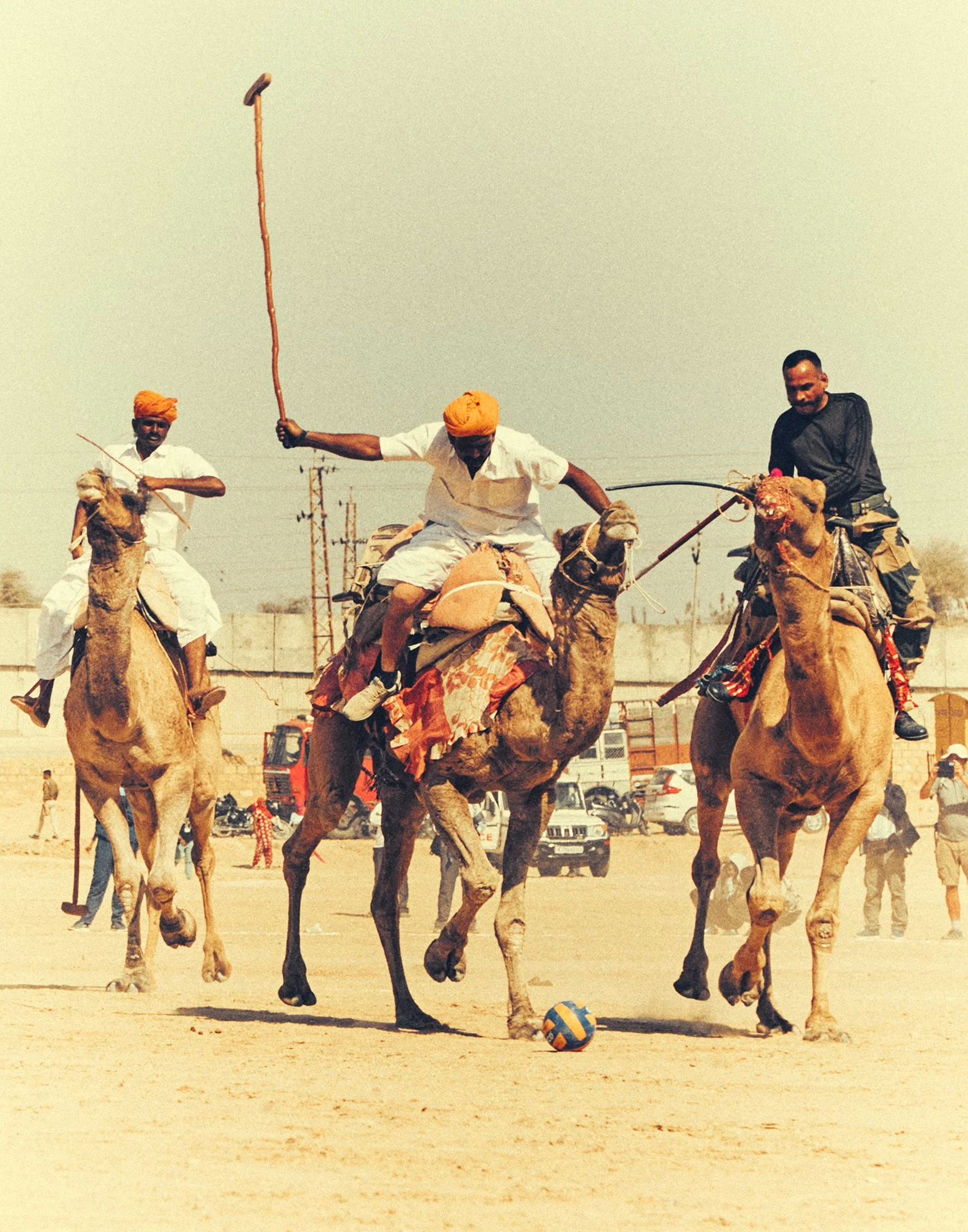

The role of the photographer has been defined as being either that of a hunter or a farmer. Hunters typically work spontaneously. They're opportunistic, they use the camera as a way of capturing a moment in time which is unpredicted. The farmer is someone who cultivates the image. My current idea is that those two don't tell us much about the photographer themselves, their subjectivity. In those two camps, the hunter or the farmer, you're not aware of the identity of the artist. Of course, they'll have a style and a theme, and thematic concerns, but they themselves are shielded by the device of the camera itself. So, it struck me that there must be a third mode, which is photography as a mode of expression.

This realisation came to me when a friend showed me some photographs he'd taken of a lake in Ireland. I knew instantly – from the tonal range, the framing, that the image was about grief. And that made me realise that it's something that I hadn't considered as a way of looking at the art history of photography. So that's what I'm currently working on. It is self-portraiture of a sort, but not necessarily. You may not see an image of the artist, but you can certainly, from the image, understand their state of being.

“You may not see an image of the artist, but you can certainly, from the image, understand their state of being.”

Iwona Blazwick

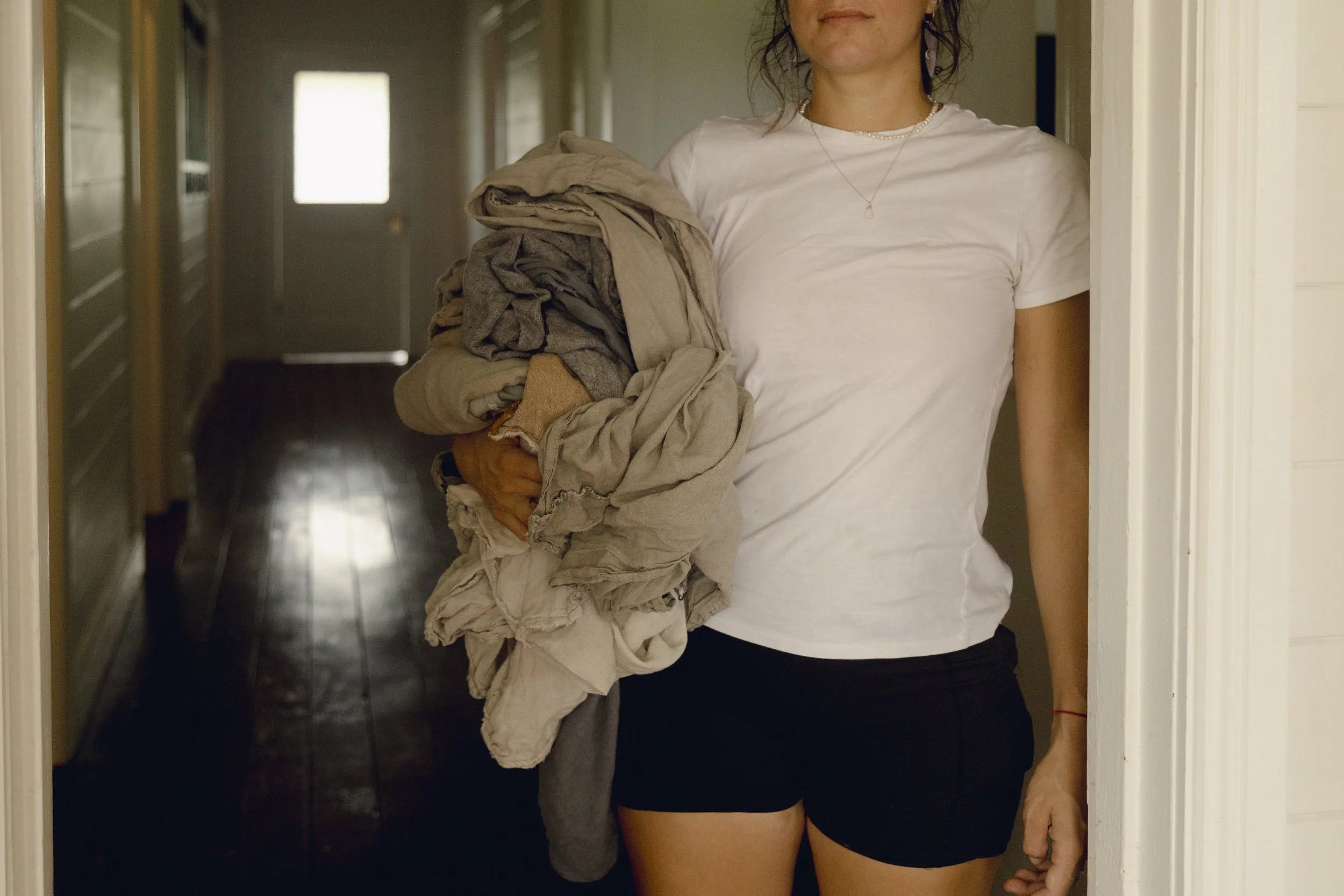

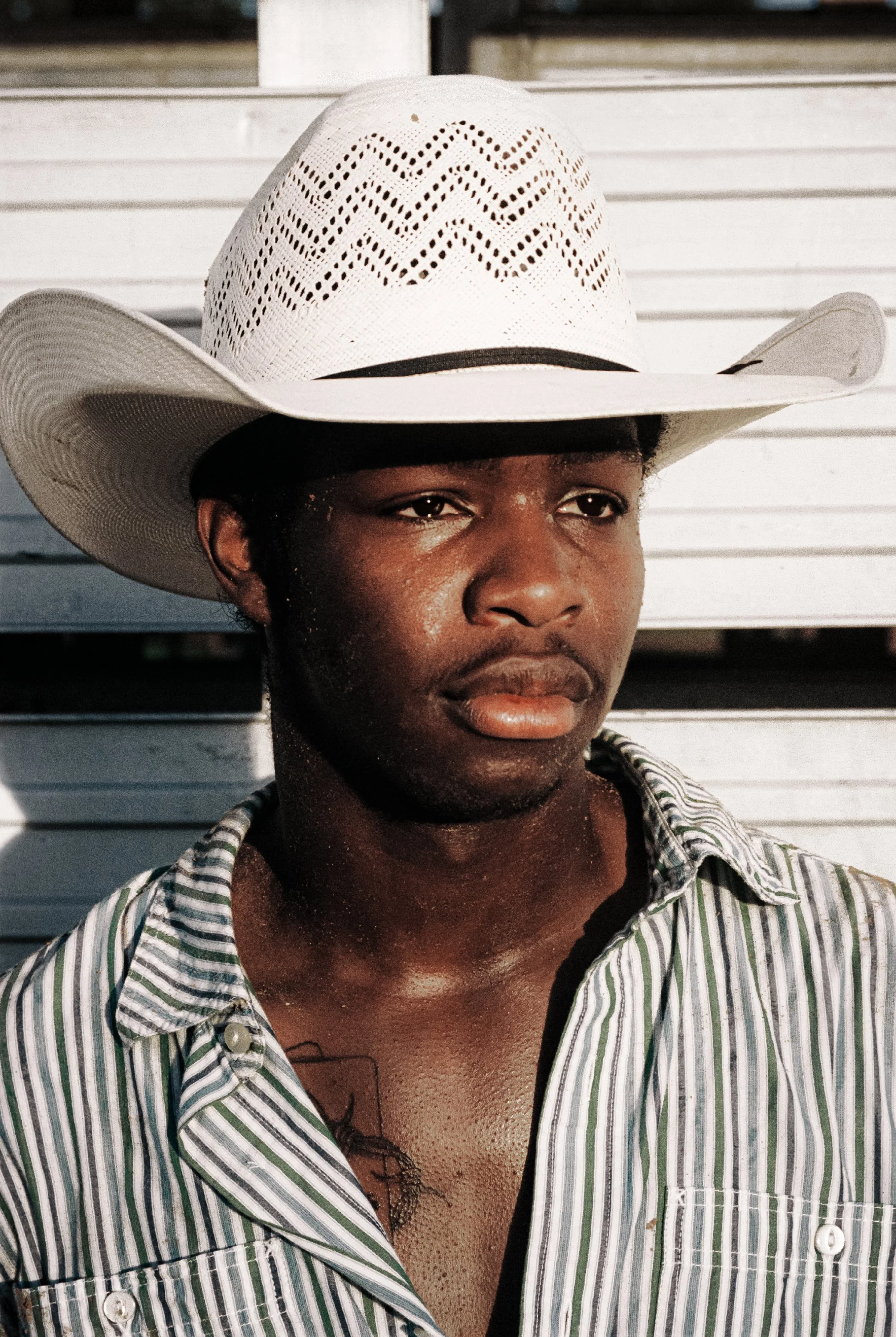

Portrait of Iwona Blazwick, Photo by Christa Holka

On the point of ‘the hunter’ versus ‘the farmer’, there is an absolutely gendered aspect of that, where street photography is considered a masculine pursuit. I think that's an aggressiveness or an invasiveness of space, of being able to walk up to a stranger and stick a camera in their face and snap a photo of them.

That's very interesting, because that also raises the issue of empathy. And either that there is a very deep psychic connection between the photographer and their subject, based perhaps on love, or joy or desire. Or alternatively, the view of the world that they present in their image is a direct corollary for their state of being. So, I think that's what I'm struggling with. I'm just trying to find at the moment how you would define that. How could an empty room perhaps signify that, or this picture of the lake that this artist, Adrian O’Carroll took. And it just seemed to me that everything about this image was right there. You didn't need to know any backstory at all. So, what were the components of that? How do we as viewers understand that?

Empathy through entirely non-human communication.

Of course, we can look at contemporaries like Nan Goldin or Wolfgang Tillmans. I think the idea about desire is definitely there, but then these more abstract, very low-key kind of imaging, which has no drama, no obvious triggers for emotional state, and yet they have this very potent atmosphere. That's what I'm sort of trying to define at the moment.

Adrian O’Carroll: Droplets

“As viewers, we don’t stand and judge or interrogate the image – we’re implicated in it. It makes us feel what the artist wants to express.”

Iwona Blazwick

Nan Goldin: Nan after being battered, 1984

How do you possibly decide the scope of what you’re curating?

So, there are three main components to this: the photographer, the artist and the image. But there is also the viewer. As viewers, are we transported into that zone that this artist is trying to express? Does the image reveal something about the consciousness of seeing? There’s a politics to that as well, because we're not apart from that image. We don't stand and judge it or interrogate it, as we do with other kinds of also brilliant images, we're implicated in it. And I think that's interesting, where we can relate to it, and it makes us feel what the artist wants to express. And how does that become an exhibition? I'm a curator. My thing is the time and space in which you read works of art, and from the moment you enter a space, what happens to you. So, it's creating a narrative. I'm curatorially still trying to figure out how this thing might evolve.

And the point you're making about the gallery space as well, you've always worked on this physically ginormous scale. The stuff you've done at the Tate is massive, the stuff you're doing in Saudi Arabia is massive. How do you navigate working in a much smaller, more able to conceptualise size?

I think sometimes one wants intimacy. Sometimes you want that absolute focus and something which is poetic and profound, and sometimes you feel expansive, and you want the thrill of something at scale which is nearer to the sublime. That's why the art world, a life in art, is so extraordinary because artists constantly surprise us. That's what's so energising about working in our field, and why I'd encourage anyone to be part of it, because it’s so unexpected. The directions in which people take, take this medium and photography is still, despite the ubiquity of all these billions of images, you still find these single images.

I think that's the other thing, when everything is locked down, it's not interesting. But when there's a sense of imminence in the image, or some possibility or something unknowable, that's when it becomes interesting. And I think that is part of this project. The feeling is, how do you capture the ineffable and the imminent and so forth.

Wolfgang Tillmans: Lutz, Alex, Suzanne & Christoph on beach, 1993

There's also another quote I think about quite a lot in relation to photography, which is that it has a fatally weak intentionality. You aren't creating a world from the ground up, as you are in other mediums, and your capacity to intentionally organise something, to say something specific, is much weaker as a result. Maybe it's the reason why it reflects more things about the people surrounding it.

It's true that there's so many variables and contingencies and uncontrollable elements that seep into the image somehow. But you're still framing, aren't you? You're still shutting out and trying to shut that noise down. But the problem with the digital world is it's so heavily mediated. You can airbrush, and you can do anything you like. And maybe that unmediated impression of the world, that index of the world, that the simplest cameras do is important. I've noticed people are really interested in cyanotypes again, box cameras, because the element of perfection seems so corrupting, somehow. Nothing is real. And somehow there's authenticity, perhaps about what a box camera or an old, you know, a proper analogue camera can do. There's going to be this shift towards all these analogue forms, and an idea about the unique, maybe the handmade beginning to be more valued. So again, I feel like we're in a position of transition now. I think also trust is the other part of this; people are now beginning not to trust the photograph. And for 100 years, it was seen as the basis of truth, and when that's gone, what is truth. I fear a new puritanism, a new kind of iconoclasm.

What does like that puritanism look like to you? In terms of where truth comes from, or the content of images themselves?

Precisely that people may just distrust the world of images, yet again. It goes all the way back to Plato. Because they are so easily manipulated, will people just reject it? What is truth? Is it going to be just pure, unmediated experience? It just feels kind of a bit medieval, but it's when people create conspiracy theories.

When do you think the exhibition is going to happen?

It's still an idea. It's a concept. But I think that's quite an interesting way of curating something, testing it out. And I know some institutions are doing that now. I know the V&A and Tate have got people together just to brainstorm a ‘what if’, and I've always enjoyed curating in that way. Where you just put forward a question.