ANTIDOTE

ANTIDOTE is a framework of five photographic series and an academic essay exploring the rise of contemporary authoritarianism. Drawing on Indigenous worldviews, Marco Vernaschi proposes empathy as a counterforce to polarised ideologies. We speak with Vernaschi about power, psychology, and resistance.

Interview JC Verona Photography Marco VernaschiAt a time when authoritarianism no longer arrives with uniforms but with algorithms, charisma, and curated outrage, the question is no longer who holds power—but why we keep giving it away. ANTIDOTE, the latest long-form project by Marco Vernaschi, confronts this shift head-on, examining how contemporary techno-authoritarianism is rooted not only in political systems, but in a deeper psychological collapse of empathy.

Bringing together five photographic series and an academic essay, ANTIDOTE looks beyond Western ideological deadlock and turns instead toward Indigenous worldviews across Latin America—societies structured around reciprocity, balance, and coexistence rather than domination. In doing so, the project proposes a radical counterforce to polarisation. Ideologies are abstract and demand intellectual submission. Values, on the other hand, grow out of lived relationships, inviting discernment rather than allegiance, understanding rather than obedience.

In this conversation with ZERO.NINE, Vernaschi speaks candidly about narcissism as a political engine, social media as an accelerant of psychological fracture, and why the ANTIDOTE to our current crisis may exist far from the centres of technological and economic power. What emerges is not a manifesto, but a warning—and a call to reconsider the values shaping the world we’re collectively building.

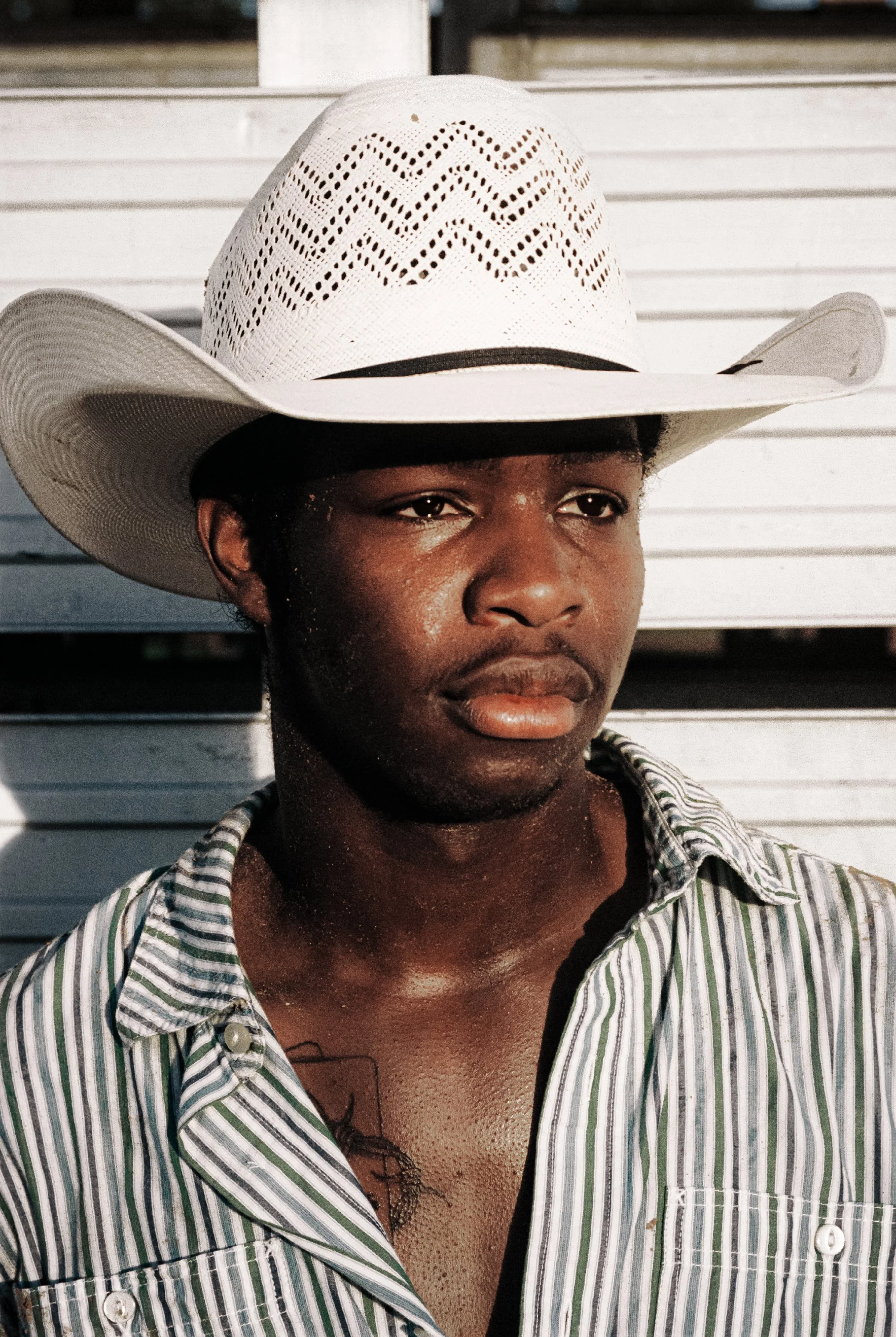

From the series The Land of Never After ©Marco Vernaschi

ANTIDOTE feels like a warning system. Did you begin it because you sensed something was already breaking in the world—or because you believed the world was already broken?

When I began working on ANTIDOTE, my intention was to engage with some of the defining issues of our time—gender equality, social justice, and climate resilience—but from a different angle: one that juxtaposes ideologies with values, specifically values rooted in Indigenous worldviews.

I’ve worked with Indigenous communities across Latin America for nearly two decades, especially in Northwest Argentina, and over time it became clear that many issues Western societies still struggle to process were resolved within these cultures long ago. Gender equality is a clear example: Andean societies have embodied values aligned with contemporary feminism for centuries—organically and without confrontation. By contrast, in the West, those same values have increasingly been captured by populist rhetoric and instrumentalised for political gain, fuelling polarisation and, ultimately, a hate-driven backlash against gender rights.

The core difference lies in worldview. Western society tends to be trapped in opposing, polarised ideologies, while Indigenous societies are grounded in human values rooted in empathy—reciprocity, harmony, and a profound respect for nature and life. Western systems are built around domination; Indigenous ones around coexistence. And domination always implies submission—and sooner or later, submission provokes rebellion.

I believe we’re witnessing a major systemic transition. History suggests that the global order evolves in roughly eighty-year cycles, beginning with periods of relative stability and prosperity that are gradually eroded by inequality and financial speculation, leading to economic collapse, debt, inflation, social unrest, and eventually revolutions and war. The current cycle, which began after World War II, now appears to be entering the early stages of this “revolution and war” phase. What makes this moment distinct is the unprecedented level of diffuse ideological polarisation—massively amplified and accelerated by social media at a scale and speed humanity has never experienced before.

You frame techno-authoritarianism not just as a political system, but as a psychological one rooted in narcissism and the collapse of empathy. Why was it important for you to approach power from that psychological dimension, instead of framing it only through ideology or economics?

Because political systems don’t emerge out of the blue—they grow out of the way a society thinks, feels and behaves. They reflect shared values, aspirations, and beliefs, and the leaders who rise to power are almost always expressions of that same cultural and moral environment. That’s why I felt it was essential to look beyond ideology or economics and locate power at the psychological level.

We’re living through an unprecedented rise in narcissism, largely fueled by a social-media-centred culture that began taking shape around 2009. And this isn’t an abstract trend—it has very real consequences in everyday life. Social media had the potential to become a tool for collective awareness and positive change, but a combination of factors—limitless greed, growing economic insecurity, and deep human vulnerabilities rooted in ignorance and insecurity—pushed it in the opposite direction.

What we’ve seen instead is the consolidation of traits typical of the narcissistic spectrum: constant comparison, pressure to perform and appear successful, hidden shame and feelings of inadequacy, an emphasis on image over substance, an obsessive need for external validation, and the commodification of the self, just to name a few. At the same time, social media has intensified emotional detachment. Many people experience it as a space disconnected from physical reality, which helps explain the normalisation of online hate and harassment. A growing body of research shows that this chronic detachment has contributed to a significant decline in empathy, especially among younger generations.

All of this spills directly into the real world. We see it in the transformation of intimate relationships, in widespread loneliness and social isolation, and, crucially, in the rise of narcissistic leaders. These figures are particularly attractive to people with low self-esteem, who project onto them fantasies of revenge, restoration, and personal reassertion. They are seduced by a language of dominance that unconsciously promises both individual and collective redemption. In that sense, a narcissistic society almost inevitably ends up choosing narcissistic leaders.

As we speak, Trump has just deployed military force abroad. For too many people, this feels shocking, yet in your essay, it reads almost as inevitable. From your perspective, is this an aberration or the logical outcome of techno-authoritarian culture?

I believe this is a multilayered issue, and it really demands discernment and a case-by-case reading. In my essay, I point to a historical pattern that tends to repeat itself whenever authoritarian leaders accumulate excessive power in socially depressed contexts. In Trump’s case, we’re dealing with someone who displays all the core traits of malignant narcissism—an individual driven by a lifelong quest for revenge.

No matter how successful or powerful his public image may seem, his inner structure is marked by a deeply fractured ego. When someone constantly claims to be “the best ever” or “the most successful in history,” that’s not confidence—it’s compensation. It’s a defensive shield against low self-esteem, inner shame, and a profound sense of inadequacy.

Narcissism exists on a spectrum, and malignant narcissists sit at its most destructive end. Clinically speaking, they are only one step removed from antisocial personality disorder, commonly referred to as psychopathy. For them, destruction isn’t a means to an end—it is the end. Leaders like Trump are drawn toward warfare because it offers both revenge and self-affirmation through destruction. That’s why they recognise no real limits—legal, institutional, or ethical—and operate in an overtly opportunistic way, exploiting any situation that serves their personal interests.

That said, the recent intervention in Venezuela requires nuance and ideological detachment. While Trump’s motivations were clearly linked to strategic control over oil and gas resources, it’s also undeniable that Maduro’s regime systematically starved, tortured, imprisoned, and killed its own population. For decades, Venezuela’s resources were effectively traded with Russia, China, Iran, and Cuba in exchange for political and military protection, with no benefit whatsoever for Venezuelans themselves.

From an international law perspective, there’s little doubt that Trump acted in disregard of it. But international law ultimately exists to protect people—and in that sense, it had already been violated continuously by Maduro’s regime for more than a decade, while much of the international community confined its response to sanctions that largely worsened civilian suffering.

So no, Trump’s move was neither sudden nor surprising. This is precisely how narcissists operate: they act out of self-interest, manipulating circumstances to their advantage. By looking at the situation beyond any ideological lens, I understand—and share—the relief and joy many Venezuelans felt at Maduro’s capture, while still hoping that a genuinely democratic transition, led by Venezuelans themselves rather than by Trump’s ambitions, can finally restore democracy to the country.

“Western systems are built around domination; Indigenous ones around coexistence. And domination always implies submission—and sooner or later, submission provokes rebellion.”

From the series Las Cienagas ©Marco Vernaschi

Authoritarianism naturally drifts toward war because it normalises conflict as a political tool. Do you see U.S. actions less as geopolitics and more as a psychological performance of domination?

More than anything, I see these moves as opportunistic and self-serving, driven less by any coherent long-term strategy than by one individual’s instincts. Trump’s claims over Greenland are a clear example. At his core, he’s a ruthless negotiator—and one who genuinely enjoys the performance, especially when backed by overwhelming economic and military power. We’ve seen this logic before, most notably in the way he imposed tariffs across much of the world. His approach is entirely goal-driven: he recognises few limits and is willing to use whatever leverage or intimidation is available to get what he wants.

Opposite him stands a largely dormant European Union, still struggling to process the sudden loss of its historic ally and protector. Europe has become a passive spectator: a war is raging on its own continent that it has been unable to resolve, its vision of global cooperation is fractured, and its leadership appears stuck in endless meetings, bureaucratic inertia, denial, and strategic confusion. From Trump’s point of view, this is the perfect setup. It allows him to make claims that once would have seemed unthinkable, using—very much in his own style—the same politics of fear that Putin has so effectively refined.

That said, I don’t believe Trump is actually willing to use military force to take Greenland. He knows he can’t, and that any such move would almost certainly put his presidency at risk. He likely won’t need to. The European Union is so fearful and paralysed that it will probably end up negotiating—just as it did over tariffs and, more broadly, over its own global relevance—under the assumption that a Russian attack is imminent and unavoidable.

Narcissists understand better than anyone how powerful fear-based gaslighting can be. But for that dynamic to work, they also need a co-dependent counterpart—and that is precisely the role Trump is assigning to Europe. In that sense, a significant part of today’s struggle over the global order is playing out on a psychological level. And that’s why understanding the psychological profiles of the leaders involved is so essential.

You describe social media and algorithmic systems as accelerators of narcissism. In that sense, do you see figures like Trump, Musk, or Milei as political leaders, or as products of the technological ecosystem itself?

Figures like Trump and Milei are before anything, the products of the societies they represent, with algorithms acting as powerful accelerators of their rise. Musk is a different case: despite his brief involvement with Trump’s administration, he’s not a political figure but an extraordinarily powerful and opportunistic tech visionary—one who unfortunately shows a troubling lack of social and individual empathy.

Still, it would be a mistake to lump Trump and Milei together. Although they share narcissistic traits, they emerge from very different contexts. Milei rose out of Argentina’s noisy TV talk shows as a histrionic outsider economist, channelling widespread social exhaustion. Awkward as he often seemed, he backed his claims with hard data and delivered them with an aggressively confrontational style that translated quickly into mass support.

When he launched his campaign, Argentina was collapsing under 298% accumulated inflation after two decades of mismanagement and corruption. Daily life had become unbearable, and people across all classes were fed up with the hypocrisy, impunity, and isolationism associated with Cristina Kirchner—later convicted in a $1 billion fraud case—while her government preached human rights and honoured dictators like Maduro. Milei understood that exhaustion and turned his outsider status and social-media-friendly aggression into political capital.

Setting ideology aside, his economic results so far are hard to ignore: inflation dropped sharply, reserves grew, poverty declined relatively, and the country moved toward stabilisation. But Milei isn’t just an economist fixing a balance sheet—he’s the President. His gains rest on shrinking the state and ending money printing, but also on brutal cuts to education, public health, and pensions, and that bill will eventually come due.

Beyond economics, his denial of climate change, hostility to social equality, and openly confrontational, hate-laden rhetoric—along with his refusal to engage in dialogue—place his leadership squarely within an authoritarian logic. In that sense, Milei remains another expression of Argentina’s oldest problem: populism, which always follows the same script—a messianic leader, a polarised society, invented enemies, and the steady delegitimisation of dissent.

“A narcissistic society almost inevitably ends up choosing narcissistic leaders.”

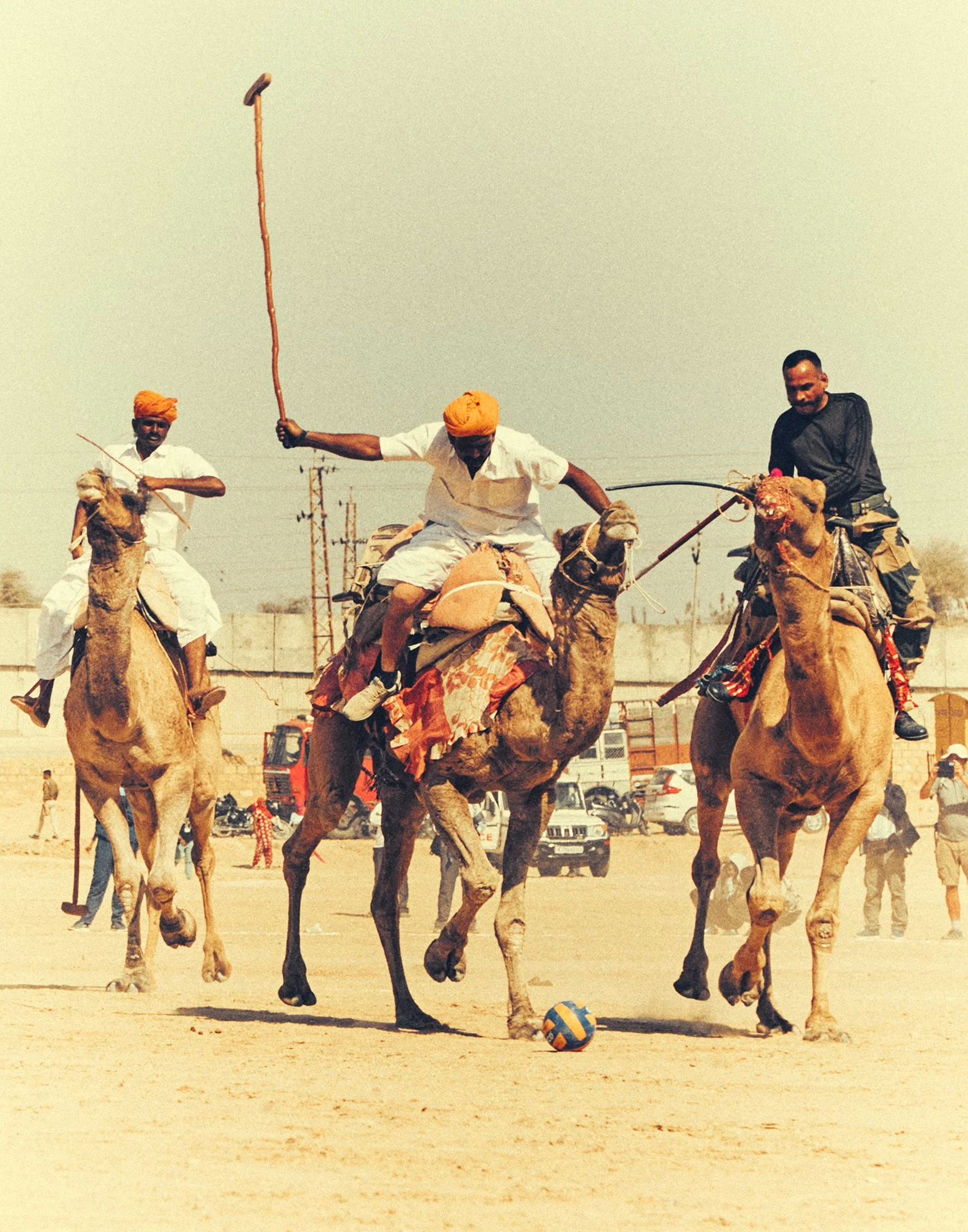

From the series Macondo ©Marco Vernaschi

Is it possible that what we call political polarisation is actually something deeper — a mass psychological condition shaped by validation, performance, and algorithmic reward?

I think the extreme polarisation we’re seeing today is the result of several forces converging at once. Social media, by design, encourages superficiality, misinformation, and the rapid consumption of events. It invites instant opinions and emotional reactions rather than reflection, context, or critical thinking. When that accelerated dynamic collides with the consolidation of opposing—and often radicalised—ideologies, it creates a particularly dangerous feedback loop.

Ideologies work through abstraction and obedience. They flatten the complexity of lived reality into rigid doctrines that create a sense of belonging by exclusion, and inevitably generate counter-ideologies and conflict. Once the mind is captured by ideology, it becomes selective in its relationship to truth. Facts are no longer used to understand reality, but filtered—or distorted—to protect a pre-existing narrative. Meaning stops flowing from facts, and facts instead become instruments of rhetoric.

There’s also another factor that’s often underestimated: ignorance. Conscious ignorance can be challenged and corrected, but unconscious ignorance is far more destructive. This is where the Dunning–Kruger effect comes in: people who lack competence often also lack the ability to recognise that lack. Popular culture reduces it to “dumb people think they’re smart,” but in reality it’s a powerful cognitive bias—one that is massively amplified by social media and ideological echo chambers.

Together, these dynamics don’t just deepen polarisation; they normalise it. And when polarisation becomes entrenched at a mass psychological level, it almost inevitably paves the way for social breakdown and, eventually, violent conflict.

While Western societies move toward techno-feudalism and isolation, ANTIDOTE turns toward Indigenous and rural communities in South America. Why did you feel the antidote to this crisis might exist at the margins of technological power rather than at its center?

In short, because these societies are organized around values rather than ideologies—values rooted in empathy, reciprocity, and peaceful coexistence. And those are precisely the values that have been steadily eroding in Western societies, replaced by indifference, radical individualism, and ruthless competition.

Ideologies are abstract and demand intellectual submission. Values, on the other hand, grow out of lived relationships. They invite discernment rather than blind allegiance, understanding rather than obedience. That distinction is absolutely central to ANTIDOTE.

The project isn’t suggesting that we all retreat into nature or start worshipping Pachamama. What it calls for is a necessary cultural correction: a move away from ideological rigidity and back toward the kind of shared values that, in the post–World War II period, helped shape some of the most advanced and prosperous democracies in the world.

By placing values above ideology, ANTIDOTE rejects the false binaries that fracture contemporary society and argues instead for a shared moral ground rooted in reciprocity. From that perspective, Indigenous worldviews are not romanticised alternatives, but a pragmatic moral compass—one that has proven its effectiveness over centuries.

What do these communities understand about empathy, land, and coexistence that the hyper-connected world seems to be losing?

First and foremost, these communities understand that social harmony is only possible when a society is intentionally structured around equality and balance. Most Western democracies were originally shaped by ideals inherited from the French Revolution—Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité—yet over time they seem to have lost sight of those foundational values. Indigenous and rural societies, by contrast, never detached those principles from everyday life.

They also understand that excessive wealth and unchecked materialism tend to generate unhappiness and conflict, especially once inequality becomes systemic. Today we’re witnessing an unprecedented divide between an ultra-wealthy elite and a rapidly shrinking middle class, to the point where just 1% of the global population controls nearly half of the world’s personal wealth.

Another key insight is the understanding that humans and nature are not separate, but part of the same living system. Natural resources are therefore treated as a common good—something to be respected, protected, and used responsibly, rather than exploited without limits.

When you look at the most urgent challenges of our time—growing inequality, the erosion of social justice, climate disruption, and escalating conflicts over natural resources—it becomes clear why we should be looking at these societies not as utopias, but as sources of wisdom we urgently need to relearn.

From the series In Limbo ©Marco Vernaschi

“Ideologies are abstract and demand intellectual submission. Values, on the other hand, grow out of lived relationships.”

From the series Ahícito Nomás ©Marco Vernaschi

Do you believe Western democracies are quietly being replaced by a new system? One where algorithms, billionaires, and tech platforms hold more power than citizens?

It’s a very Orwellian way of putting it, and while there’s some truth there, I don’t believe consolidated democracies can simply be replaced overnight. What we’re seeing isn’t a sudden takeover but a deep, ongoing transformation—one that’s still unfolding and far from inevitable. For that reason, I remain cautiously hopeful.

Historically, every major technological shift has sparked apocalyptic fears. It happened during the first and second Industrial Revolutions, and it’s happening again today with AI. What changes isn’t the reaction, but the tools through which power is exercised. Long before science and technology, mass control relied on brute force and religion. If you look closely at the structure of major religions—Christianity or Islam, for example—you find a similar, clearly control-oriented narrative: obedience in this life in exchange for reward in the next. That model worked for centuries.

As science took hold, it gradually eroded religious authority and, in many ways, replaced it. Technology emerged from science as a tool for progress and social advancement. The problem began when technology became infrastructural—when it stopped being something we simply use and became something we depend on. At that point, it ceased to be neutral.

Today, technology is arguably the most powerful instrument of mass influence ever created. What makes AI particularly unsettling is the prospect of systems that don’t just mediate power, but exercise it with a degree of autonomy. Still, it would be a mistake to blame technology itself. These systems are designed, trained, and ultimately governed by humans.

The real issue, in my view, is greed—specifically a hyper-narcissistic form concentrated in the hands of a small group of tech billionaires whose power now rivals, and often bypasses, democratic institutions. The key question isn’t what technology can do, but which values guide those who control it. It’s easy to imagine a very different present—and future—if algorithms were built to educate, reduce inequality, or address climate collapse, rather than simply maximise profit and attention.

At its core, this is a human crisis before it’s a technological one. Democracies aren’t being replaced by machines; they’re being slowly hollowed out by human choices and the wrong set of values. Technology may amplify power, but it doesn’t decide how that power is used. That responsibility still lies with us.

If someone reading your essay feels disturbed rather than comforted, what would you hope they do differently the next day —as a human being living within this system?

I think the reality we’re all inhabiting is disturbing; my essay is simply an analysis of that reality, so if it unsettles people, I actually see that as a meaningful outcome. Like most of my work, ANTIDOTE isn’t designed to reassure or soothe. It’s meant to offer a critical point of view—one that people are completely free to embrace, question, or reject.

What makes your question particularly interesting is that, visually, the project feels quite reassuring, almost innocuous, while the essay is intentionally challenging. That deliberate contrast is meant to expose the tension between two radically different realities and worldviews.

As for what I’d hope people might do differently, I don’t really have expectations in that sense. I think it would be naïve—and to some extent pretentious—to imagine people would change their point of view based on my work. If anything, I’d be genuinely glad if even a single person were able to connect with the core values the project is trying to foster.

For instance, I’d be especially glad if it encouraged people to question the inherent blindness of ideologies and move toward more independent thinking. That alone would be a huge step forward—one we urgently need at a global level.

About Marco

Marco Vernaschi is an Italian visual artist, creative director and producer best known for his thought-provoking visuals and inspirational campaigns. He developed a variety of projects in different fields, ranging from documentary to advocacy and contemporary art. Marco’s work integrates several private and museum collections, and is featured globally in the most respected media outlets.

Marco is the recipient of numerous grants and awards, including the World Press Photo (2010). In 2015 he joined The Photo Society, of which he’s currently a member.

To see more of Marco’s work, check out his website or follow him on Instagram