AHÍCITO NOMÁS

In 2021, Marco Vernaschi produced AHÍCITO NOMÁS, investigating the link between ancestral and contemporary feminism in Argentina’s Andean Altiplano.

By Marco VernaschiNatividad Valdiviezo · Single Mother

Natividad poses for a portrait with her three months old baby, Nahir, by the mountains of Quebraleña. She's Rosita Lamas’ half-sister, a skilled goat farmer and resilient single mother of three. After Nahir was born, the father of the child abandoned both. Since then, Natividad lives in isolation, in the middle of a desert plateau by the edges of a salt flat (Salinas Grandes). She spends most of her days looking after her baby and working with goats, while her two other children Claudio and Leonardo, whose fathers also abandoned, live nearby in Quebraleña, at the school’s dormitory. Being a single mother in the Altiplano is rather common; like many other women in the region, Natividad is raising her children alone, helped by her sister and close relatives.

Argentine writer Héctor Tizón, described the feeling of being in the Andean Altiplano rather effectively: “Here the earth is hard and sterile; the sky is blue and empty, and it’s closer than anywhere else. In this land, where it is hard to breathe, people depend on many gods”.

Most of all, the Andean community relies on women (warmi, in Quechua) and worship Pachamama, supreme goddess and universal Earth Mother. A woman, life itself, Pachamama embodies all the core values that define the essence of Andean Cosmovision – a point of convergence between religious and social beliefs, and the philosophical foundation of the rights of nature.

“Ahícito Nomás tells the story of inspiring matriarchs, community leaders, teachers, LGBT activists, and violence survivors.”

Cosmovision advocates the sacred link that connects humans to the cosmos, fosters gender equality and embeds a strong set of woman-centered values that celebrate femininity. Not surprisingly, the Altiplano's society is regulated since the pre-Columbian era by an evolving matriarchal system that remarkably anticipates the current wave of feminist values that is reshaping most societies around the world.

Ahícito Nomás tells the story of inspiring matriarchs, community leaders, teachers, LGBT activists, and violence survivors. In different ways, all empowered women who, through their personal stories, reveal a multifaceted, resilient society where ancestral and contemporary feminism meet to make a difference.

Rosita Lamas · Matriarch

Rosita is a quiet but firm matriarch, mother of six girls and financial mastermind of a large family. She was born in the Puna but now lives in Huacalera, in the Quebrada de Humahuaca, where she manages her farm. Rosita is a respected community member and, to her extended family living in the Puna, the strategic bridge enabling primary goods and vegetables trade between the two valleys. Besides taking care of her six children, two nephews and the farm in Huacalera, Rosita also manages a big herd of llamas representing one of her family’s main sources of income. Every week, she travels to Quebraleña to visit her sister Natividad and take care of the animals, while her husband Alfredo works as a miner in the South of the country.

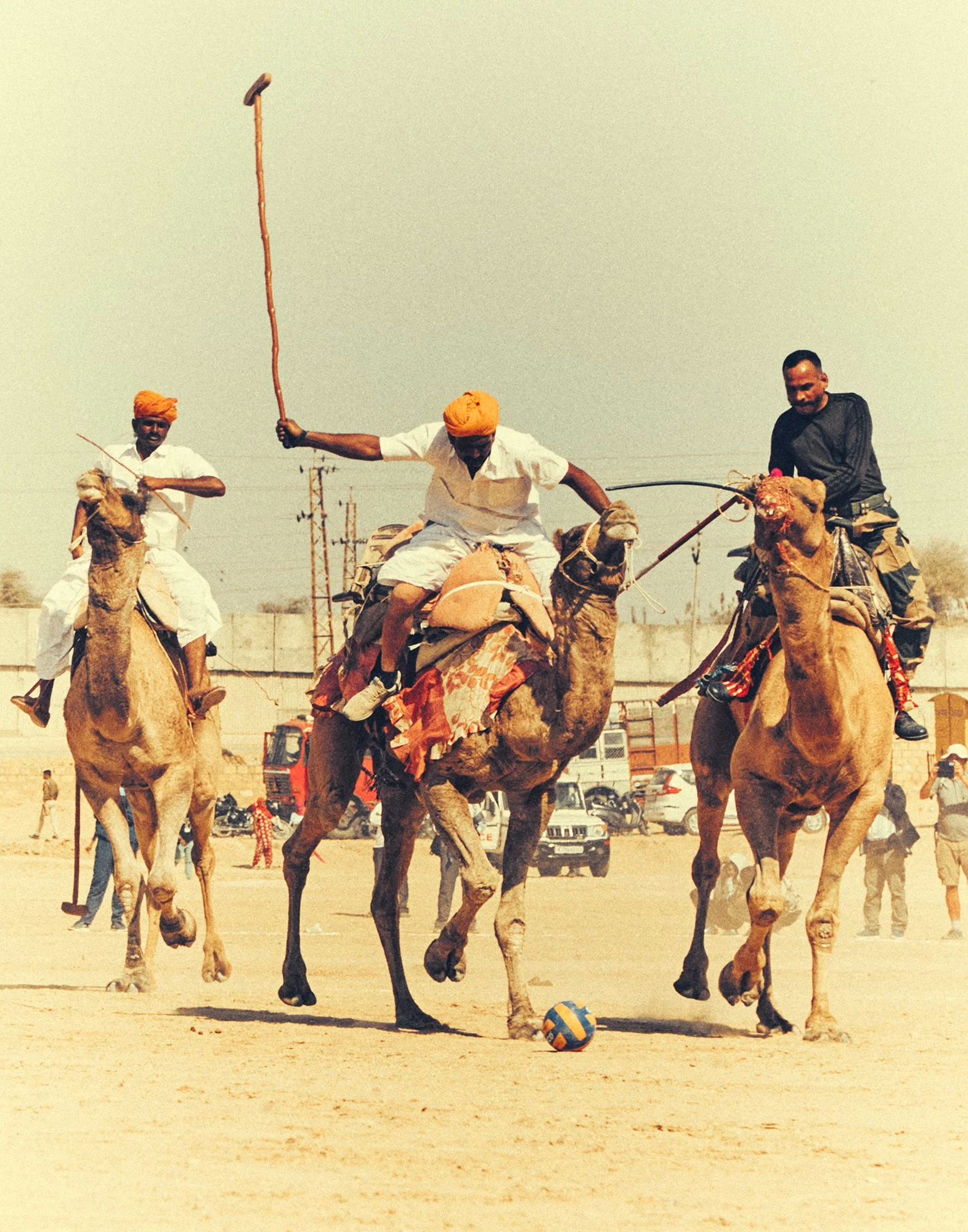

Altiplano

The Andean Altiplano is the most extensive area of high plateau on Earth outside Tibet, stretching across Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina. The Argentine portion of the Altiplano, where this story unfolds, is divided in two sub-regions: the lowlands, known as Quebradas – and the highlands, called Puna. Casabindo, in the picture, is a remote village located at 12000 feet in the Puna. Argentine writer Héctor Tizón, described the feeling of being there better than anyone: “Here the earth is hard and sterile, and the sky is closer than anywhere else. In this land, where it is hard to breathe, people depend on many gods”.

Dominga Lamas · Traditional Healer

Dominga poses for a portrait holding a dried llama fetus, minutes before starting a Pachamama ritual offering. She lives in Quebraleña, where she’s a key community member and the driving force behind any important decision to be made within the Lamas family. Besides being an experienced wool farmer, Dominga inherited from her mother extensive knowledge in traditional medicine and serves her community as a healer, leading most celebrations and rituals. Before starting ceremonies, she typically puts two coca leaves underneath her eyes to demand Pachamama’s blessing and guidance. Traditional healers in the Altiplano are typically women like Dominga. They play a central role in Andean society and are revered by other community members as ambassadors of Pachamama.

Save Your Soul

The Salva Tu Alma cross is a ubiquitous reminder of the Altiplano’s colonial past. The cross was first introduced by Jesuit Missionaries around 1550, with the goal to convert travelers to Christianity. It was typically placed along remote roads, by isolated churches that occasionally offered asylum to travelers. As the conquistadores begun to build villages and towns, natives were offered free housing and work in the fields, but had to convert to Christianity first. Indigenous culture has been humiliated for centuries; until a few decades ago, schools would ban Quechua encouraging families to educate their children in Spanish. Eventually, Christianity and cosmovision have blended into the vibrant, syncretic culture that we know today.

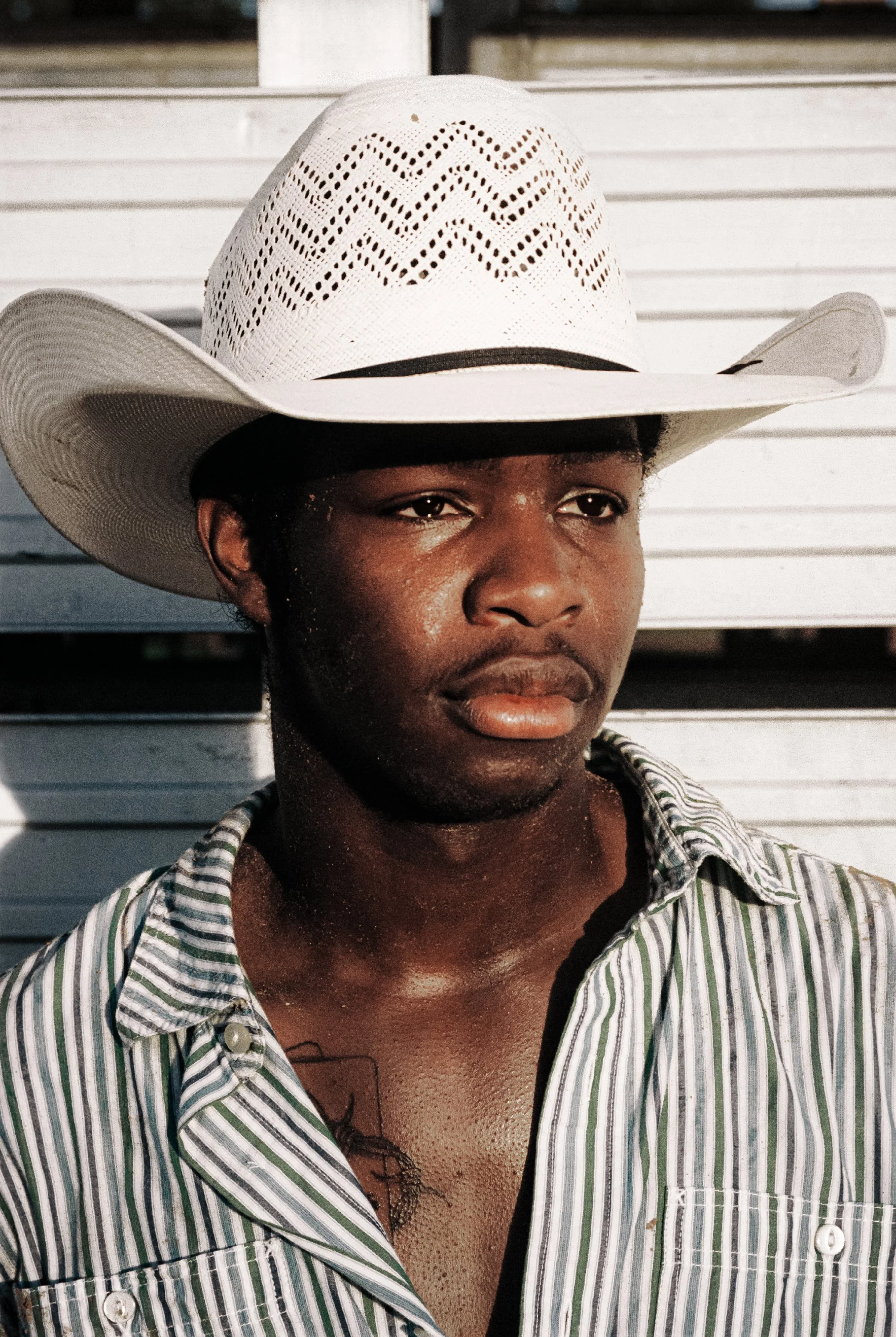

Nahuel Lamas · Aspiring Naturalist

Nahuel is 11 years old, and loves animals. He’s Patricia’s youngest son, spontaneously propelled by curious enthusiasm toward the natural world, starting of course with the two horses that his family own. Thanks to his mother’s teachings and love for the gaucho culture, he’s learned take care of a horse in every possible aspect, from taming to riding. Women typically play a crucial role in passing on the gaucho tradition, as they are responsible to educate their children according to the values and practices of the group. Besides farm animals though, Nahuel dreams to learn about more exotic species, such as elephants and lions. In the portrait, he’s riding Patricia’s horse on a jaguar saddle crafted by his grandfather, who hunted the feline.

“To keep the socio-demographic spectrum as meaningful as possible, I focused on four large family groups during a period of 100 days. All families descend from the same dynasty, the Lamas, and live in two different subregions of the Altiplano.”

Patricia Lamas · Community Leader

Patricia poses for her portrait mimicking the iconic "We Can Do It" gesture, a universal symbol for gender equality, conveying her commitment on women's rights. Patricia is a community leader and mother of four. She's a domestic violence survivor who successfully managed to rebuild her life. After struggling for more than a decade with an alcoholic partner – and overcoming cancer in the process – Patricia reborn from the ashes, landed a great job and now thrives as a touristic entrepreneur. Her resilience and personal story contribute to inspire several other women in her community; in 2021, she was eventually elected leader of La Huerta, where she lives with her new supportive partner Martin, and her four children, Camila, Facundo, Emanuel and Nahuel.

White Horse

The white horse is a strong cultural symbol throughout the Andean Altiplano. Horses arrived to South America beginning of 1531, with the Spanish conquistadores, and soon became an epic character in local pop-culture. In the Argentine Altiplano, where the gauchos originally formed, the white horse symbology is eloquently controversial. The interpretation differs in two versions, revealing two antithetic perspectives: the indigenous’ – who believe the white horse is a potentially malicious creature (the Devil is gringo, and rides a white horse), and the gauchos’ – who revere and acknowledge the animal as a symbol of bravery and distinctive social status.

Dayra Vigabriel · LGBT Activist

Dayra is afraid of having just two years of life ahead. Despite being full of energies and good health, she’s now 34 – and life expectancy for transgender people in Argentina is estimated around 36. Dayra’s best friend Lourdes Ibarra, who recently passed away, died precisely at that age. Together, they created Damas de Hierro (Iron Ladies), a LGBT organization based in Jujuy that provides housing and support to hundreds of transgenders fleeing from violence and discrimination. Since the departure of Lourdes, Dayra is focusing most of her time on a law bill aimed to protect the rights of transgender workers, hopefully to be approved by the National Chamber of Congress.

The Southern Gate

The Argentine Altiplano stretches through the western portion of the provinces of Salta and Jujuy, at the extreme Northwest of the country. Its southern access is considered to be the Quebrada de las Flechas, a mesmerizing canyon located between the towns of Cafayate and Angastaco (Salta). Here the legendary Ruta 40 runs along the Calchaqui Valley crossing the enchanted gorge, protected as a Natural Monument. The canyon has an intricate labyrinth of gullies and ravines with vertical and angled walls. The interplay of sunlight and the rocks’ shadows causes its appearance to change as the day progresses, making the Southern Gate a magical place.

Lorena Suruguay · Historian

Lorena poses for a portrait during a gaucho festival where she helps prepare food. A proud ambassador of her cultural heritage, she defines herself as a progressive-conservative historian who likes to rethink traditional values into a fresher perspective. Lorena works at the Mountain Infantry Regiment School where she teaches history. In pursing her vocation as an educator, she focuses on replacing the established macho narrative by revealing the untold role of women through South American history. She’s a member of La Gauchita, a cultural organization created exclusively by and for women, where she earned the title of paisana, a distinction conferred to women who excel in farming practices and rural etiquette.

About Marco

Marco Vernaschi is an Italian visual artist, creative director and producer best known for his thought-provoking visuals and inspirational campaigns. He developed a variety of projects in different fields, ranging from documentary to advocacy and contemporary art. Marco’s work integrates several private and museum collections, and is featured globally in the most respected media outlets.

Marco is the recipient of numerous grants and awards, including the World Press Photo (2010). In 2015 he joined The Photo Society, of which he’s currently a member.

To see more of Marco’s work, check out his website or follow him on Instagram