ICONS – Martin Parr: The Kitsch and the Lurid

Martin Parr’s aggressively colourful depiction of British life sparked enormous debate about what it meant to be British, and how as a deeply classist country we understand our own relationship to visualisations of class. We reflect on his revolutionary work after his recent passing.

Words Holly WycheGarden open day, from The Cost of Living, 1986-1989

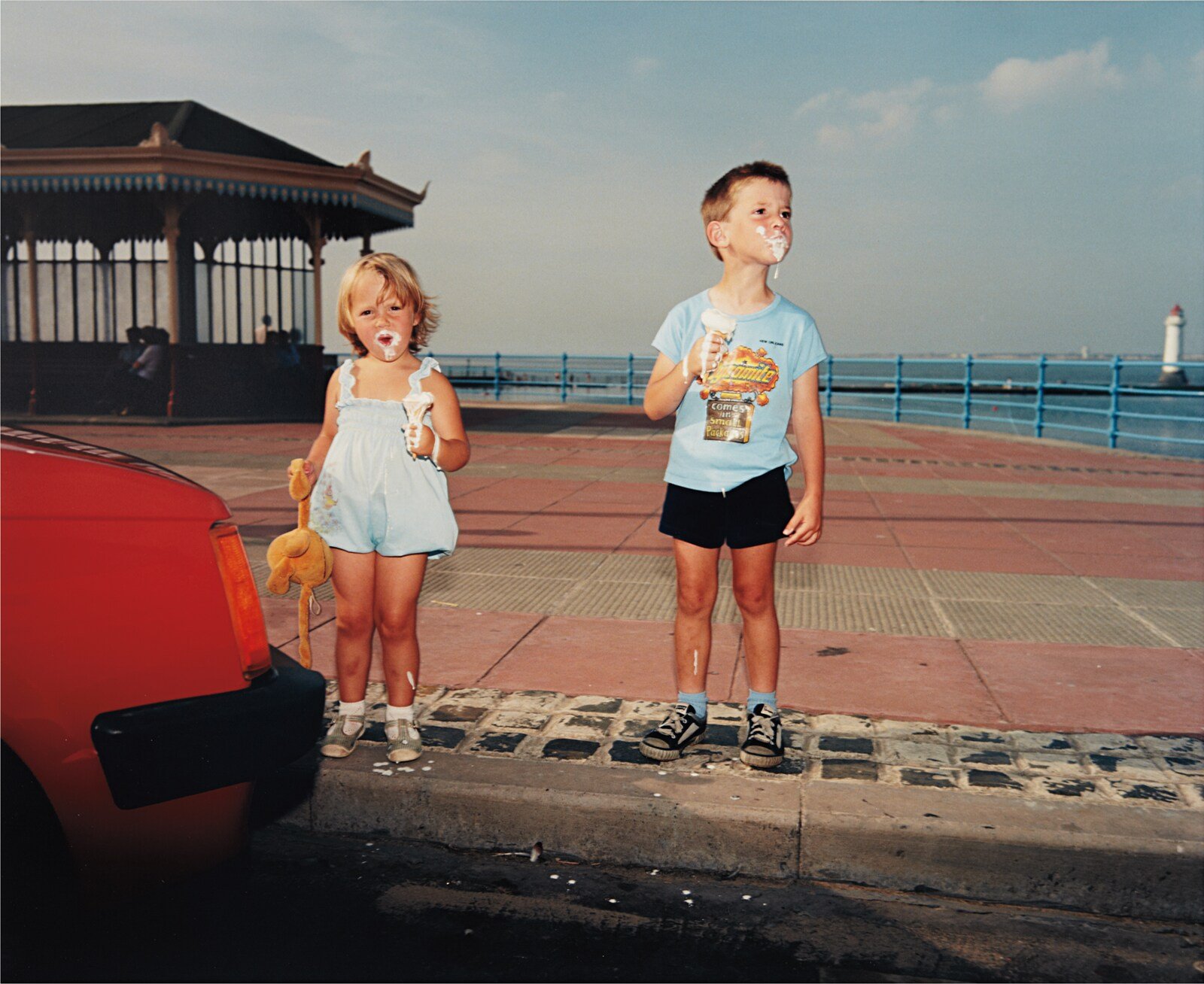

How much does your personal relationship to class affect your understanding of the art you see? Do photos of the upper class show them as pretentious or refined, and do equivalent photos of the working-class seem tinged with sympathy or pride? More importantly, how much of this reaction comes from the photographer’s relationship to class, or from your own? This is the question that’s defined Martin Parr’s career. His work is almost tastelessly vibrant, replete with colour in a way that resembles a vintage seaside postcard but with none of the romance. His beaches are grotty, its residents are garish, and there’s far more concrete than sand. He has an irreverent and unavoidably un-chic idea of what it means to be British, a nationality that to Parr is primarily defined by their ability to unload the entirety of a cornetto directly onto their shirts on a tepid day.

“I create fiction out of reality. It’s the subjective nature of photography. The only thing that matters is your relationship to the subject. That’s what you’re in control of. It’s all true, but it’s my truth. My personal truth.”

As a result, his work has at times been divisive. It’s been understood to either reflect an ineffable part of British life that is our love for the tacky, or at worst, gawk and laugh at this tackiness as a symptom of a less refined working-class existence. This isn’t a schism unique to Parr’s work, but what’s interesting in the case of Parr is why specific types of people respond to his work in the way they do.

Auction of Harvest Festival, 1978

Hebden Bridge, Crimsworth Dean Chapel Anniversary service, 1976 / Sowerby Bridge Mouse Show, 1978

Commuter, Tokyo, Japan,1998

The most well-known anecdote about this regards the collection pictured, Parr’s seminal work, “The Last Resort”. It was first shown in Liverpool to a working-class crowd, similar to the subjects of the photos. Neil Burgess, curator of the exhibition, said locals thought the depiction of the Thatcherite era, seaside England was ‘hysterical’ and that ‘we didn’t have any complaints from people who saw themselves in those pictures at all.’ Issues instead surfaced when the work was later shown at the Serpentine Gallery, to a snobbier audience who were the first to deride Parr’s depiction of the seaside as exploitative and demeaning. Audiences were apparently taken aback at how lurid his work was. How could he possibly depict people as living such a gauche life? This sentiment is where the issue fundamentally lies. Is Parr’s work demeaning, or do Serpentine socialites think it is because they believe the lives themselves are demeaning?

“When I started working in colour, suddenly my work was seen as a critique of society rather than a celebration. There’s something inherently romantic about black and white, whereas colour made it all the more real.”

First photo taken by Martin Parr

Parr took his first photograph at age 11 of his father standing on a frozen lake. Since that first photo, taken in 1963, he said “nothing else was going to happen” other than becoming a photographer. The photo was taken during Saturday birding walks to Hersham Sewage Works where he and his father would fastidiously catalogue creatures and stuff specimens. A dead mole Martin’s father found and taxidermized was a prized possession in Parr’s basement museum growing up. A lot of people posit that his approach to photography, one that Parr defined as a form of collection, came from his bird-watching parents.

“If you want me to do a book on dogs, no problem. I can come up with 100 pictures straight away. Or cigarettes. I’ve just done a book called No Smoking using my archive, edited by my gallery here in London.”

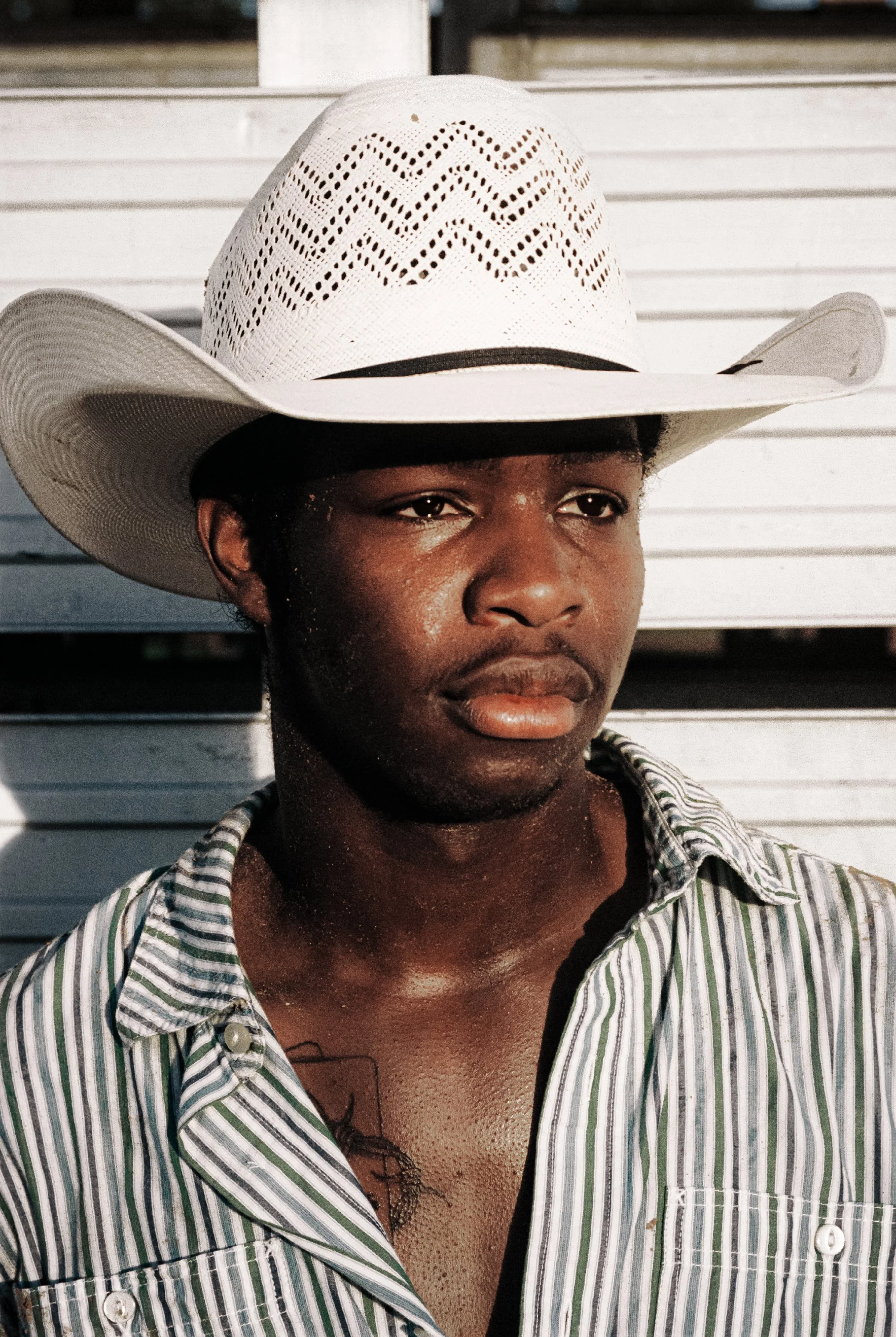

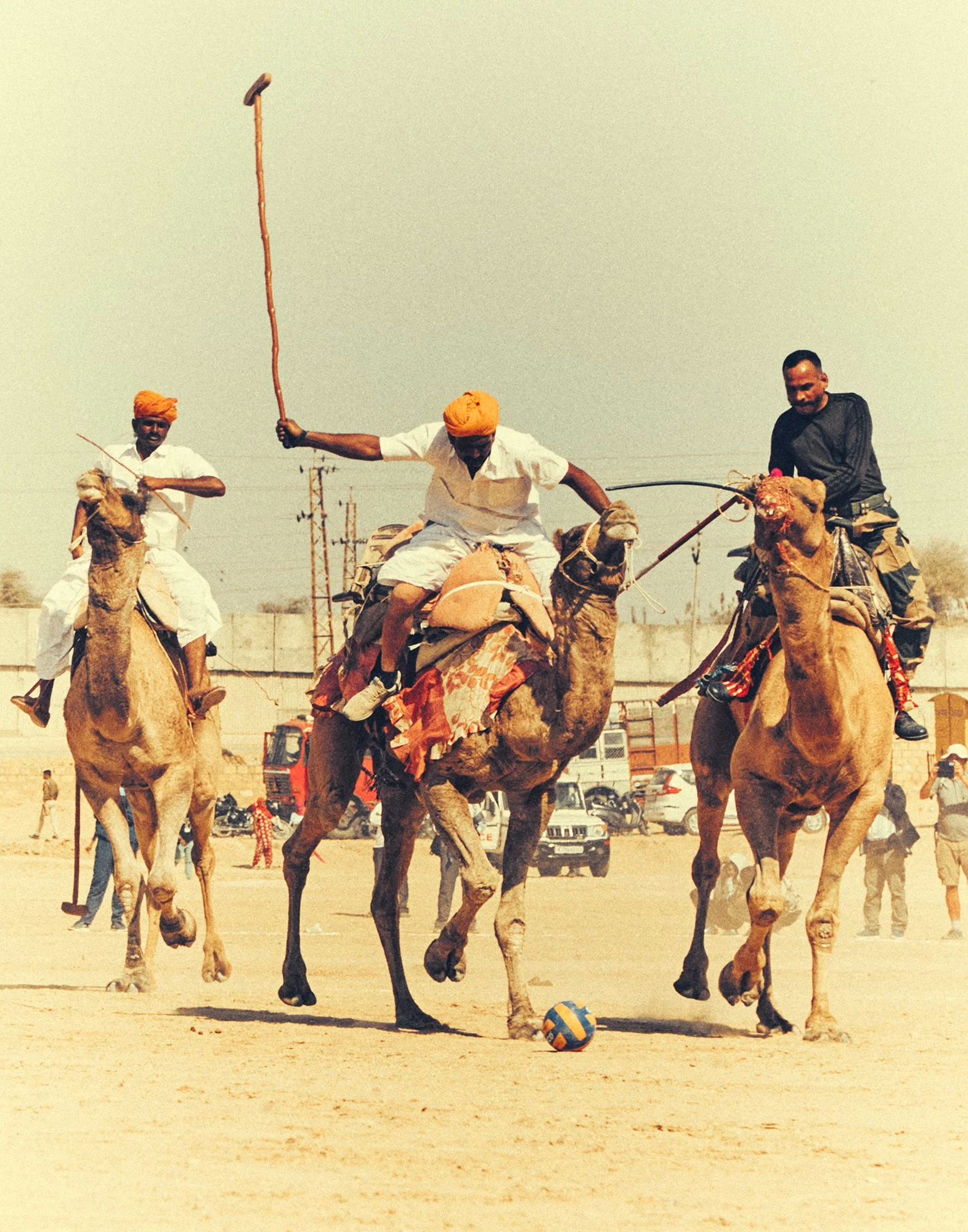

Parr believed photography doesn’t inform or “save the world”, it itemises it, and he catalogued life dearly. In this way, he was more of an archivist than an aesthete, and you can see this in the things he personally collected. Ephemera like Saddam Hussein watches and porcelain plates with designs regarding the miners’ strike cramped his home. The rhythms of his photographic style also reflected this historically British love for birding. He wandered gently, ‘hung about’ and waited for a specific moment to present itself as opposed to jamming himself into situations where he didn’t fit and disturbing the natural order. As a result, Parr seemed genuinely at home, and deeply adoring of, the places some considered him critical of. In the documentary ‘I am Martin Parr’, he sits on a quintessentially British train and chugs along with it, mimicking the train’s rhythm. He loved being in this environment. What’s expressed isn’t sympathy or disdain, it’s the perspective of an observant man who’s spent a lifetime collecting vignettes of a patently bizarre country he loved dearly.

Kings cross station, 1990

Knock, Ireland, 1996

The last resort,1983-1985

“I like the craziness of the English, with all their hobbies and their interests. The race meetings, the agricultural shows, the summer fêtes. We are an eccentric lot.”

This kernel of love at the centre of his work is what prevents it from being a demeaning depiction of the people featured. He loved these things, and this is what separates Parr out from a lot of the photography that tries to do what he’s done. This doesn’t even come from Parr’s imitators’ misunderstanding of his work. It’s more that a lot of amateur photography now unknowingly emulates an irreverence that Parr first popularised. One of the most basic instincts of the modern photographer, to juxtapose slightly comical elements of modern life, arises because he’s genuinely “changed the way we see”, a phrase that is now synonymous with Parr. There are fantastic professional photographers who have shades of Parr that we’ve featured at ZERO.NINE, but what separates them from Parr is that they are now a little more cynical. Zed Nelson’s award-winning collection, “The Anthropocene Illusion” features a similar critique of the tackiness of modern life through our desire to replace natural spaces with artificial spaces that mimic them. His photos are incredible, but have a more pessimistic note to them that is entirely understandable with the state of the world. Parr himself began to become slightly more pessimistic towards the end of his life, stating, "The state we're all in is appalling. We're all too rich. We're consuming all these things in the world. And we can't. It's unsustainable.” Before his death in late 2025, he released a similar collection to Nelson’s work titled ‘global warning’ that feels somehow heavier. Regardless, what was so moving and special about Parr was that he never dismissed gauche and tacky consumption as the bum note at the end of human existence. In a way, it is the defining element of ‘the future’. And it isn’t slick or appealing in the way we imagined the future might be, but it’s objectively human. Precisely because of its vulgarity.

“You have to have that belief early in the morning before you go out, that this could be the day when something happens,”

Chichén Itzá, Mexico, 2002

If you want to find out more about Martin Parr and his legacy, please follow the official Instagram account, visit the Magnum website or the Martin Parr Foundation