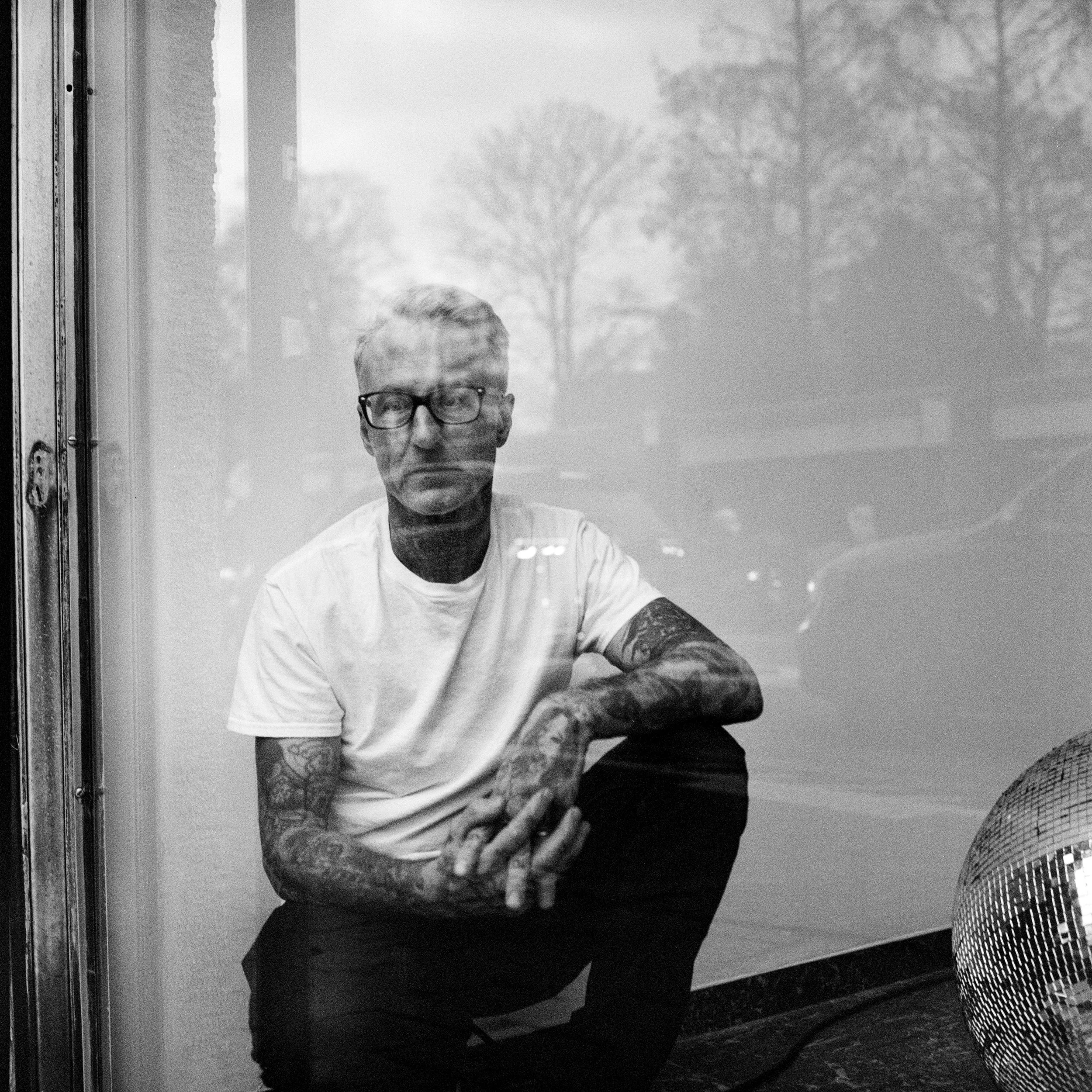

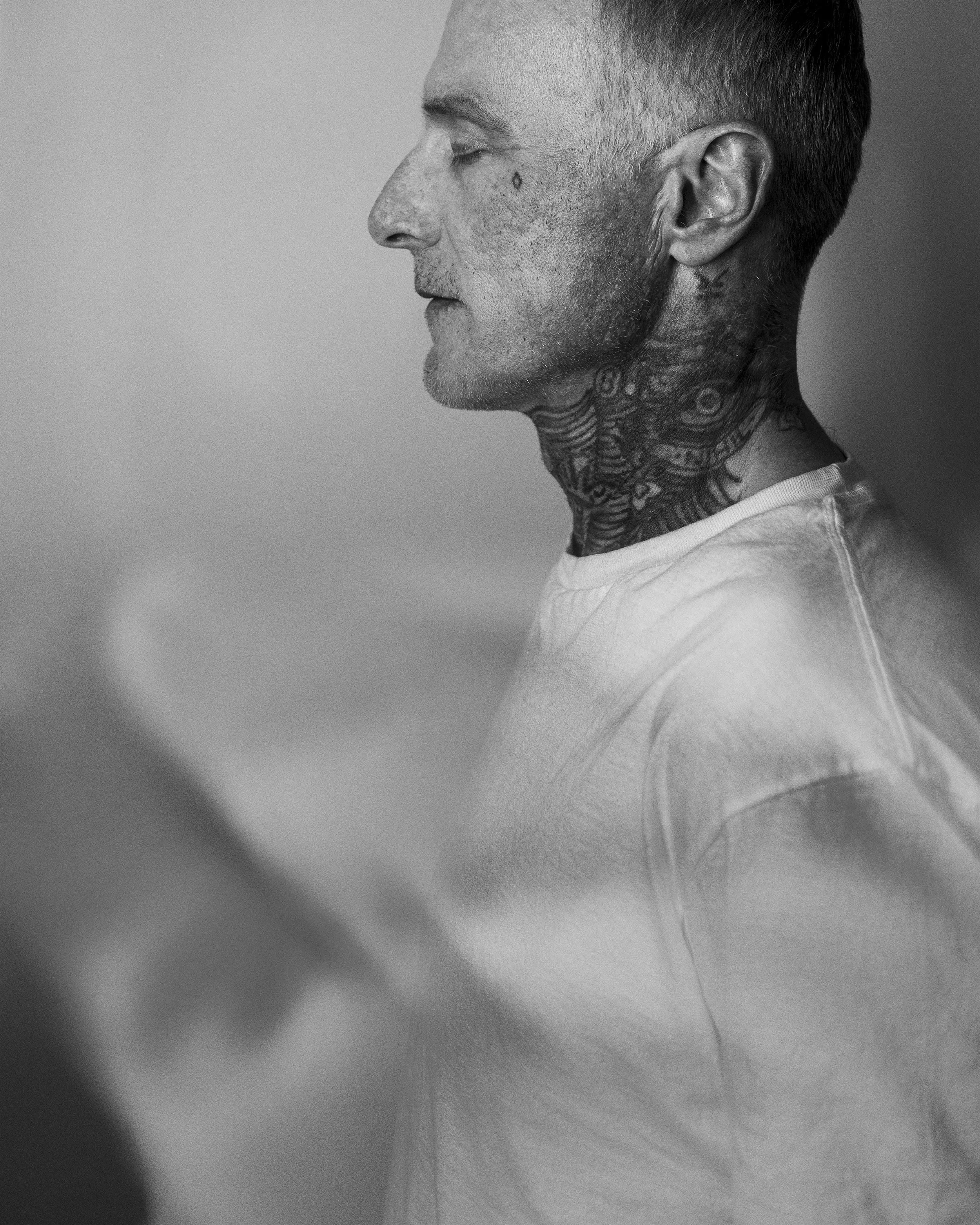

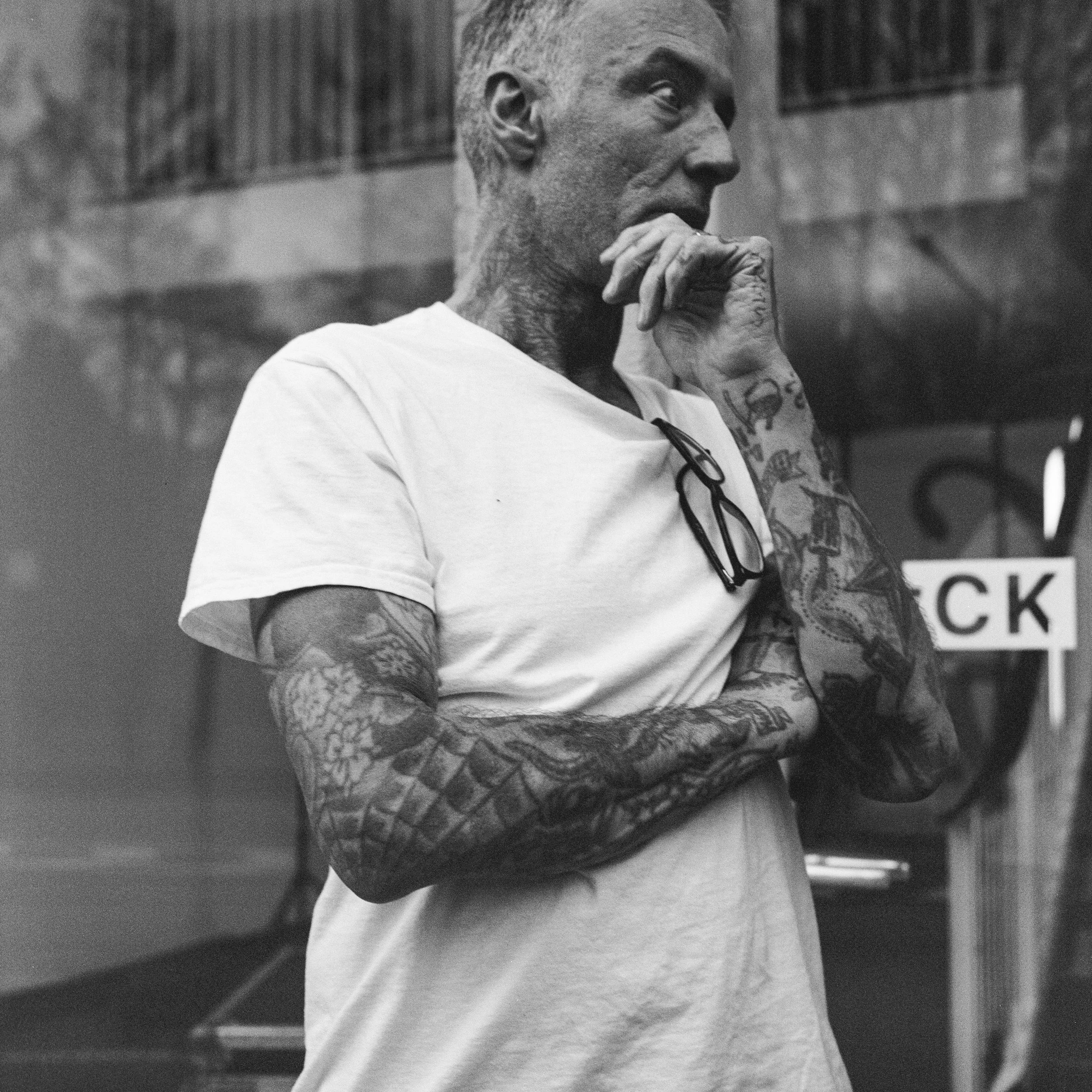

Banks Violette – When Loss Becomes Art

A fire glows behind the glass of TICK TACK in Antwerp, poised between comfort and destruction. It feels like a signal between welcoming yet alarming, stopping passersby in their tracks. From the darkness, a backwards sign reads The End, marking the threshold of Wish You Were Here, the recent exhibition by Banks Violette, curated by Maria Abramenko. On the eve of the opening, amid final checks and quiet tension, we spoke with Violette about grief, sound, and the collapse of America.

Interview Giulia Piceni Photography Christian TrippeIt has been a few years since, like in Homer’s Odyssey, you left the adventurous New York only to return to Ithaca, metaphorically and literally your hometown. Has the making of this show made you feel as though you were coming back home, to something familiar and deeply cherished?

Maybe not cherished, but familiar. Ithaca feels like a kind of non-space. Unlike New York City, it lacks a recognisable identity and is defined by absence. That absence gathers meaning, projections, and interpretations. The show is about that process, how meaning forms around absence.

Producing art from the margins undeniably marks a punk approach. Can one be subversive without making noise, and create chaos while remaining immersed in stillness?

Yes, absolutely. It comes from where I am from. Growing up in the middle of nowhere, there was no built-in audience. You had to create not just the work, but the conditions for its reception. That shaped how I understand subcultures and making work. Everything had to be built from the ground up. Returning to a place like that, where I have a history of creating audiences and events from nothing, feels more intuitive than New York ever did.

Is this absence of an audience and consequent lack of immediate feedback that feels freeing for you?

No, it is not. When those moments do happen, when someone truly relates to what you are doing, you value them far more. In places like New York, Antwerp, or any large city, people are conditioned to recognise certain things as important. There is already a structure telling you that this matters. But when that response comes from a place without a built-in system for circulating ideas, and people still respond, you know it is genuine. You know it is really connecting. There is something fragile and beautiful in that rarity. I treasured it then, and I still do now.

“The basement functions like a grave, a descent into the opening of a film that never continues.”

Banks on grief, spatial symbolism and the exhibition’s structure

Moving to this show in particular, the TICK TACK space is intentionally left empty. In moving through it, one encounters a void that is only apparent. How did you conceive emptiness as a spatial and emotional device within this exhibition? If loss cannot be framed, how can absence be used as an organising principle?

The central question of the show is loss. For me, it begins with a specific event: my friend and hero Steven Parrino died in an accident after leaving my house on New Year’s Eve. The next morning, the year began with his death. Those moments sit atop one another, separated by an unreachable absence that becomes the connective tissue of the exhibition. In the basement, a video reconstructs a work Steven described, but I never saw. I know its content, but not how it would have been realised. The basement functions like a grave, a descent into the opening of a film that never continues. The show is built around that structure, around endings, absence, and what can never be fully accessed.

You were mentioning the basement and as a matter of fact, the show has been divided on a total of three levels, two of which are occupied by the work The End. Does this spatial fragmentation mirror something bodily or temporal, like breath or rhythm? And how does this relate to your ambivalence toward the gallery as a closed system?

The End is fragmented and does not exist in a single place, moving like a wave. The show works outside the gallery too, from the street, at night, on your way home. Inside, it becomes something else. I have always been ambivalent about galleries, and this exhibition resists containment. The text at the front overlays the outside world, acknowledging what lies beyond the walls. It avoids a sealed gallery experience and relates directly to the outside through reading, positioning, and perception.

“A void is not something you sit in, but something you build meaning around.”

Banks on absence and meaning

The exhibition is haunted by people and memories that have lingered in your mind since leaving their earthly form. What has helped you most in coping with the process of grieving? And if grief is never fully absolved, is the cathartic power of art enough to keep going?

On its own, no. I do not think art is enough by itself. I have always been ambivalent about it, more something I felt excluded from than comforted by. I strongly resist the idea of treating emptiness or void as a meaningful posture in itself. I find that inhuman. For me, absence demands an active response. A void is not something you sit in, but something you build meaning around. That act of construction, of refusing passivity and insisting on making, is the only response to grief that makes sense to me.

In this exhibition, there is the permanent feeling of having ghosts here around, particularly in the basement, as you were mentioning. In what way does the material figure that appears in the globe function within the narrative and emotional structure of the exhibition?

This piece refers to Parrino’s unrealised idea of using the 1936 Universal Pictures opening animation. What you see downstairs is a complete digital reconstruction of that logo, remade from the ground up, working with the music video director Zev Deans (Mayhem, Behemoth, Lamb of God, etc). We designed it so the text is always on the edge of legibility but never fully readable. It feels close to comprehension, then slips away. Like recognising the outline of a disaster without fully understanding it, the animation seems about to resolve, but never does.

It is also very theatrical. In that sense, why did you feel the urgency to adopt such a tone in this exhibition, almost in the way of tributing the silver screen as well?

The show is built around a specific absence, a single evening, but it also speaks to much more. The country I am from feels like a nightmare, and the private disaster at the heart of the show mirrors the broader world. A personal tragedy played out publicly is not unlike the logic of American politics, where domestic disasters spill into the world and we are forced to witness them. And the national language has never been English, it is entertainment. Using film grammar and theatricality frames this American apocalypticism and makes the private and public resonate immediately.

In that sense, since your work uses so much American imagery, and given the current political climate, how do you see these symbols evolving in your practice?

I often return to the same images. I am not drawn to invention for its own sake, but to a single image that can hold multiple layers of meaning, like a flag, a horse, the end, the globe. Right now, I am trying to process the collapse we are witnessing. I experience it directly as an American citizen. My wife was adopted from Vietnam, a citizen without a birth certificate, and I watch in Minneapolis as people are driven from their homes to places that feel like concentration camps, simply because their legal status mirrors hers. My response is rage, sorrow, grief. Like the absence at the core of the exhibition, there is an absence in my understanding of national identity. I do not have full answers, but this work is a way to access those questions and start a conversation that extends beyond an American audience.

“When people said after 2016 that this is not who we are, that felt infuriating. This is exactly who we are, shaped by genocide, slavery, and endless conflict.”

Banks on America and its collapse

The End echoes throughout the exhibition and also through the way you speak about the present moment. To quote Jim Morrison, This is the end / Beautiful friend. Do you experience endings as definitive, or as something capable of shifting into another form?

I do not think there is such a thing as a happy collapse. This is not something to celebrate. But so many of the systems we are trying to preserve are built on deep injustice and exploitation, benefiting only a few. I keep asking what preservation even means right now. Maybe the only outcome left is acceleration, an acknowledgement that we are already heading toward the wall. I do not have answers or a plan. I am not a theorist. I make art, and all I can do is register how this moment feels. Part of that feeling is wanting it to end, because the slow version is unbearable. When people said after 2016 that this is not who we are, that felt infuriating. This is exactly who we are, shaped by genocide, slavery, and endless conflict. The end does not feel abstract. It feels inevitable, something we have been moving toward for a long time. Maybe all that is left is to acknowledge it and stop pretending it came out of nowhere.

The catastrophe that we are witnessing will leave just death around, a ghost lingering in the void that the destruction has brought along. That same emptiness in your show. But in this case there is also something filling that void materially, which is the sound. How did that process evolve, and how collaborative was it between you and Stephen O’Malley?

Sometimes things happen by happy accident. I have known Stephen for a long time and we have collaborated several times, the first one being twenty years ago. For this show, he suggested a track from a previous project recorded in Brussels. When I heard it, it was exactly how I had imagined it. The piece is structured around an acoustic phenomenon called phase cancellation, where sound waves one hundred eighty degrees out of phase create a sense of emptiness, almost like the beating of wings. In the exhibition, this mirrors the visual and spatial design. Upstairs, downstairs, inside, outside, the objects are positioned to cancel one another out formally and pictorially, and the audio does the same. Stephen tuned everything over two and a half days, shaping how the music moves through the space. In the highest room, it feels open and bright, but as you descend, the space closes in and the sound amplifies that sensation, almost architecturally guiding your experience of the show.

“The piece is structured around an acoustic phenomenon called phase cancellation, where sound waves one hundred eighty degrees out of phase create a sense of emptiness, almost like the beating of wings.”

On the music, designed by Stephen O‘Malley for the exhibition

That is a great alignment between two minds. There is one element we have not discussed yet, which is the disco ball on fire. Can you tell us a little about the genealogy of that piece? I know there is a tradition in New York around it for New Year’s Eve, so I imagine it is closely connected to that.

The Times Square New Year’s Eve countdown features the ball as its central element, lit up and descending during the televised celebration. It used to be covered in Swarovski crystals. Like a Christmas tree at Christmas, the ball drop is a public marker for the end of the year. My disco ball reference draws on that, but it is also more universal, a symbol of celebration and witnessing collapse from the ground level. The flames are fuelled by propane, not jets of fire, but a slow, smouldering burn.

Paradoxically heartwarming, it feels like a bonfire.

Yes, it is like the hangover phase of a fireplace. Everything softens and gets fuzzier at the end. It is visible from the street, meant for after the celebration when things have gone slightly wrong. At the same time, it speaks in the language of entertainment, the American road, the billboard, the sign. In blunt terms, it carries the weight of mental collapse, a kind of reckoning. For me, that is the only time a single gesture is truly interesting. Here, it works: simple, direct, and mostly devastating.

Wish You Were Here is on show at TICK TACK in Antwerp 23. January –21. March 2026. The site-specific exhibition by renowned American artist Banks Violette features an immersive sound work by Stephen O’Malley (Sunn O)))). Visit the gallery’s website for more information or follow Banks Violette on Instagram.

Team credits

Interview: Giulia Piceni

Photography: Christian Trippe

Curated by: Maria Abramenko

Location: TICK TACK