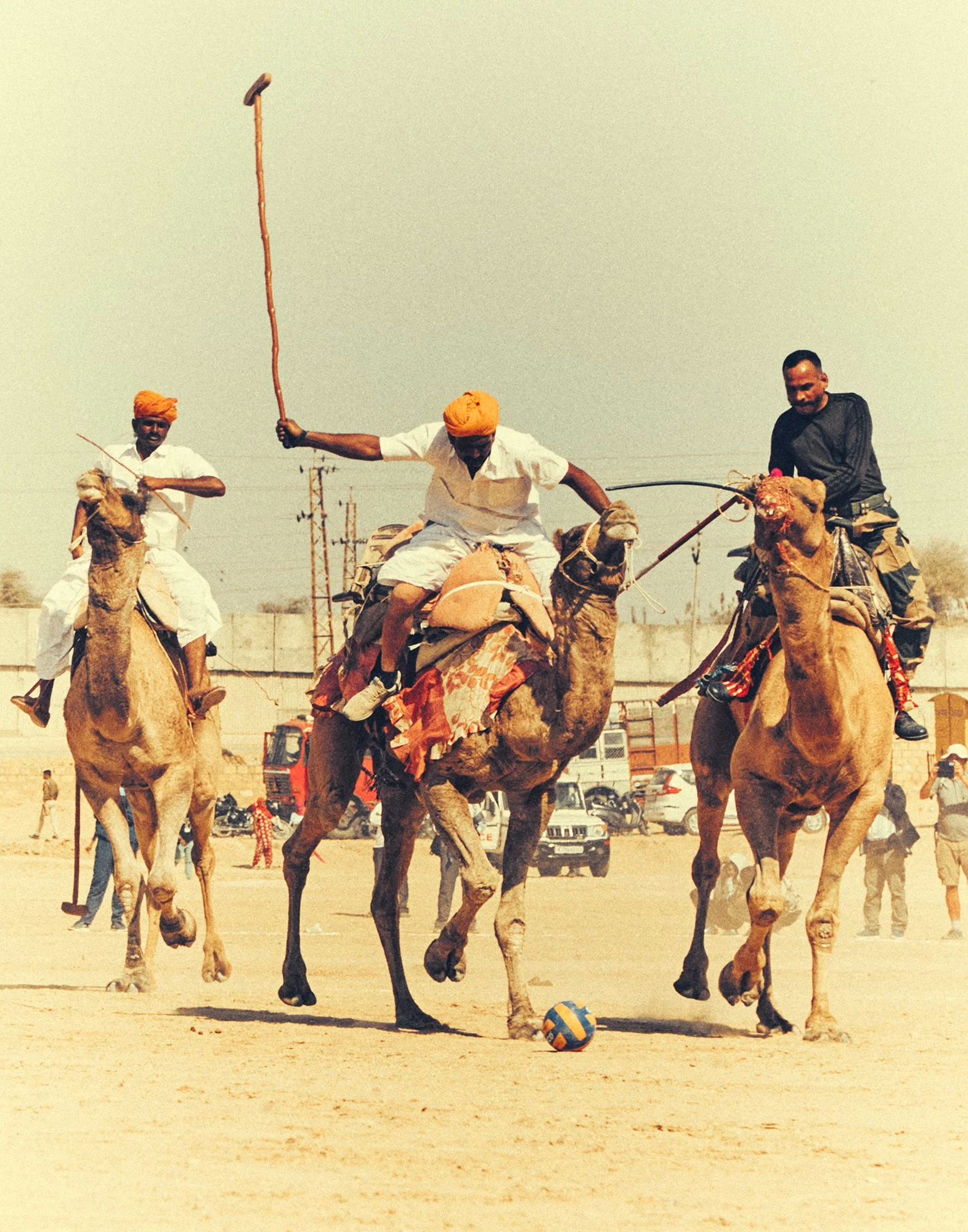

The Last Stand

Between 2010 and 2014, photographer Marc Wilson travelled to 143 locations across the British Isles and Northern Europe to capture physical remnants of the Second World War. His captivating images transport us into another time – eerie landscapes, abandoned structures and the absence of humans create a parallel universe of a time gone by. His book The Last Stand has just been published in its 4th edition and is available now.

Photography Marc WilsonHayling Island, Hampshire. England. 2013

During an air raid in April 1941, Sinah Common, a decoy site on Hayling Island, attracted more than 200 German bombs and parachute mines intended for Portsmouth. Some sections of the Mulberry harbours used on the D-Day beaches were built on the island.

In late 1943 and early 1944, Hayling Island-based COPP survey teams, trained as frogmen and canoeists, were taken by X-Craft mini-submarines and dropped off in two-man collapsible canoes three to four kilometres off the coast of Normandy. After paddling closer to the shore, the reconnaissance man swam to the beach, while the second commando stayed in the canoe conducting offshore surveillance. They recorded every detail of possible landing sites and assault areas, and information about the German enemy defences. A geological assessment of the beach was also vital, including the gradient of the underwater approaches. Core samples of the sand and gravel were taken to find out whether heavy armed vehicles and tanks would be able to negotiate the terrain. These commandos returned on D-Day, when they guided the Allied ships to the landing beaches.

The Last Stand aims to reflect the histories and stories of military conflict and the memories held within, set against a landscape formed by rising sea-levels, coastal erosion and increasing storm activity.

Photographed between 2010 and 2014, the series is made up of 86 images and documents some of the physical remnants of the Second World War on the coastlines of the British Isles and Northern Europe. Some of these locations are no longer in sight, either subsumed or submerged by the changing sands and waters or by more human intervention. At the same time others have re-emerged from their shrouds. Over the four years, 23,000 miles were travelled to 143 locations to capture these images along the coastlines of the UK, The Channel Islands, Northern & Western France, Denmark, Belgium and Norway.

Studland Bay I, Dorset, England. 2011

In April 1944, after months of intensive planning and practice, a full-scale D-Day rehearsal for the Normandy landings was held in Studland Bay. ‘Exercise Smash’, in which live ammunition was used, was watched from Fort Henry, a nearby reinforced concrete observation bunker, by King George VI, Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces General Dwight D Eisenhower.

Portland, Dorset, England. 2011

The Verne Battery was built in 1892 in a disused stone quarry on the Isle of Portland in Dorset as part of Britain’s coastal defences. Decommissioned in 1906, it was used after WW1 for storing field guns brought over from France, and during WW2 to house ammunition in preparation for the D-Day landings. It also became an AA battery (anti-aircraft artillery). Thousands of gravestones were hewn from Portland Stone for the fallen Allied soldiers who died in both World Wars. It was also used to build the Cenotaph in Whitehall.

The Last Stand, which includes both the photographs and detailed research text into the locations, was first published in November 2014. With close to 4000 copies already sold a new 4th edition has just been published and is available directly from Marc Wilson here.

Cramond Island, Firth of Forth, Scotland. 2012

An anti-submarine barrier, known as ‘the dragon’s teeth’, was built along the causeway between the village of Cramond and Cramond Island. Arranged in a long row, these pyramid-shaped concrete pylons – up to three metres high and spaced at 1.5 metre intervals – have vertical grooves in their sides into which were slotted reinforced concrete panels. On top of the blocks were fixing rings for large-diameter steel wire and anti-submarine nets.

“The Last Stand aims to reflect the histories and stories of military conflict and the memories held within.”

Newburgh I, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. 2012

A one-kilometre-long anti-tank wall was built across Newburgh’s sand dunes, 100 yards inland. This barrier consisted of a mound of sand, a deep ditch and a large wall made from steel scaffolding poles. It was designed to protect a gun battery up in the dunes from any flanking attack by tanks managing to get through the main defences on the beach.

Lossiemouth II, Moray, Scotland. 2011

A line of defences ran along the Moray coastline between Cullen Bay and Findhorn Bay through the Lossie and Roseisle forests. Anti-tank blocks ran the full length of this part of the coast, forming a barrier with the pillboxes that were placed between them at regular intervals. Some of the defences were constructed by a Polish army engineer corps stationed in Scotland.

Kazimierz Durkacz, a medical student who joined the Polish forces, wrote: “At first, we used wood to make the moulds for the large concrete blocks and then a combination of corrugated iron and wood... I remember mixing concrete with a shovel.”

Wissant I, Nord-Pas-De-Calais, France. 2012

Wissant II, Nord-Pas-De-Calais, France. 2012.

Wissant means ‘white sand’ in Dutch (wit-zand). From the 7th to the 14th century, it was considered to be part of Flanders and the local language was called ‘Old Dutch’. During the Middle Ages, it was a major port of embarkation for England until, towards the end of the 12th century, it became silted up by the shifting sands. Some historians believe that it was from Wissant that, in 55 BC, Julius Caesar sailed for his invasion of Britain. During WW2, the Germans believed the Allies would regard Wissant, the closest point on mainland Europe to the English coast, as an ideal beach for an invasion. Situated between Cap Gris Nez and Cap Blanc Nez, it was heavily fortified with enormous bunkers, blockhouses, minefields, an anti-tank wall and long-range guns that could reach the English coast. In 2013, these German defences were removed by the local authorities.

Saint-Palais-sur-mer II, Charente-Maritime , France. 2014

Saint-Palais-sur-Mer lies at the mouth of the Gironde estuary, which was defended by two fortresses built by the Germans. Like other fortifications at major harbours, they were to be defended ‘to the last man'. They were part of the ‘Atlantic pockets’, the final resistance areas, which the Germans held long after the rest of France had been liberated by the Allies in 1944.

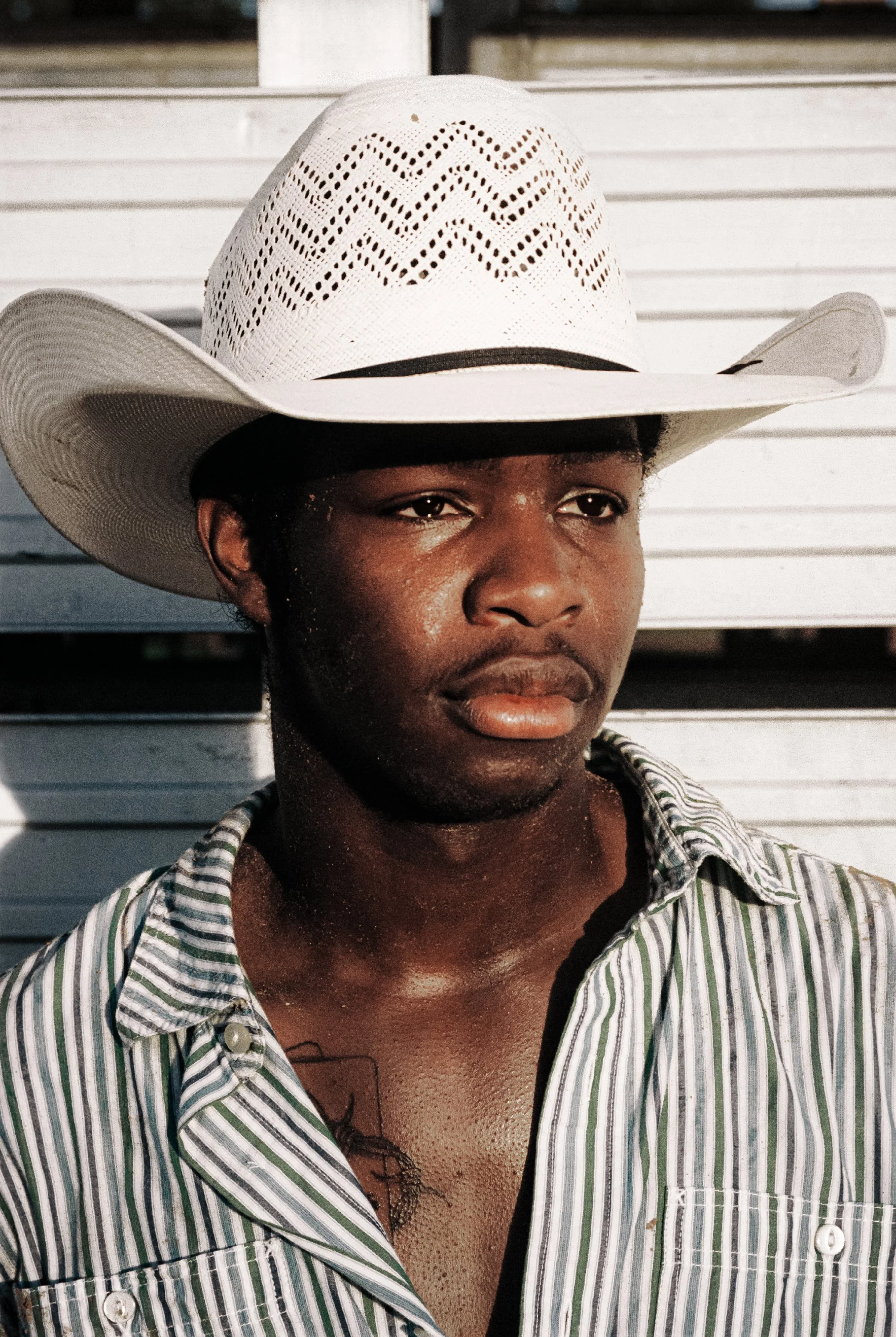

About Marc

Born in London, his studies took him from sociology to photography and he has been making photographs ever since. Marc’s images document the memories, histories and stories that are set in the landscapes that surround us. Based in the UK, he works on long term documentary projects, including ‘The Last Stand’ (2010-2014), ‘A Wounded Landscape – bearing witness to the Holocaust’ (2015-2021) and his recently completed work ‘The Land is Yellow, the Sky is Blue’ (2021-2023).

His work has been published in journals and magazines ranging from National Geographic, FT Weekend and The British Journal of Photography and Raw Magazine to Wired and Dezeen.

Marc also works as a visiting lecturer at various universities in the UK and has given talks about his work both in the UK and abroad including France, the South Pacific and Japan.

To see more of his work, visit his website or follow him on Instagram