Alana S. Portero: Bad Habit and Beyond

Alana S. Portero’s transgender coming-of-age novel Bad Habit recently celebrated its second anniversary after runaway success. Recently featured on Dua Lipa’s ‘Service95’ book club and praised by renowned director Pedro Almodóvar, Portero’s book speaks to a vulnerable life lived at a dangerous time. Bad Habit follows the narrator’s life in 1980s post-Franco Spain and the influential people in her life, almost all marred as abject in some way or another. We met with Alana during a live event organised by Romancero Books.

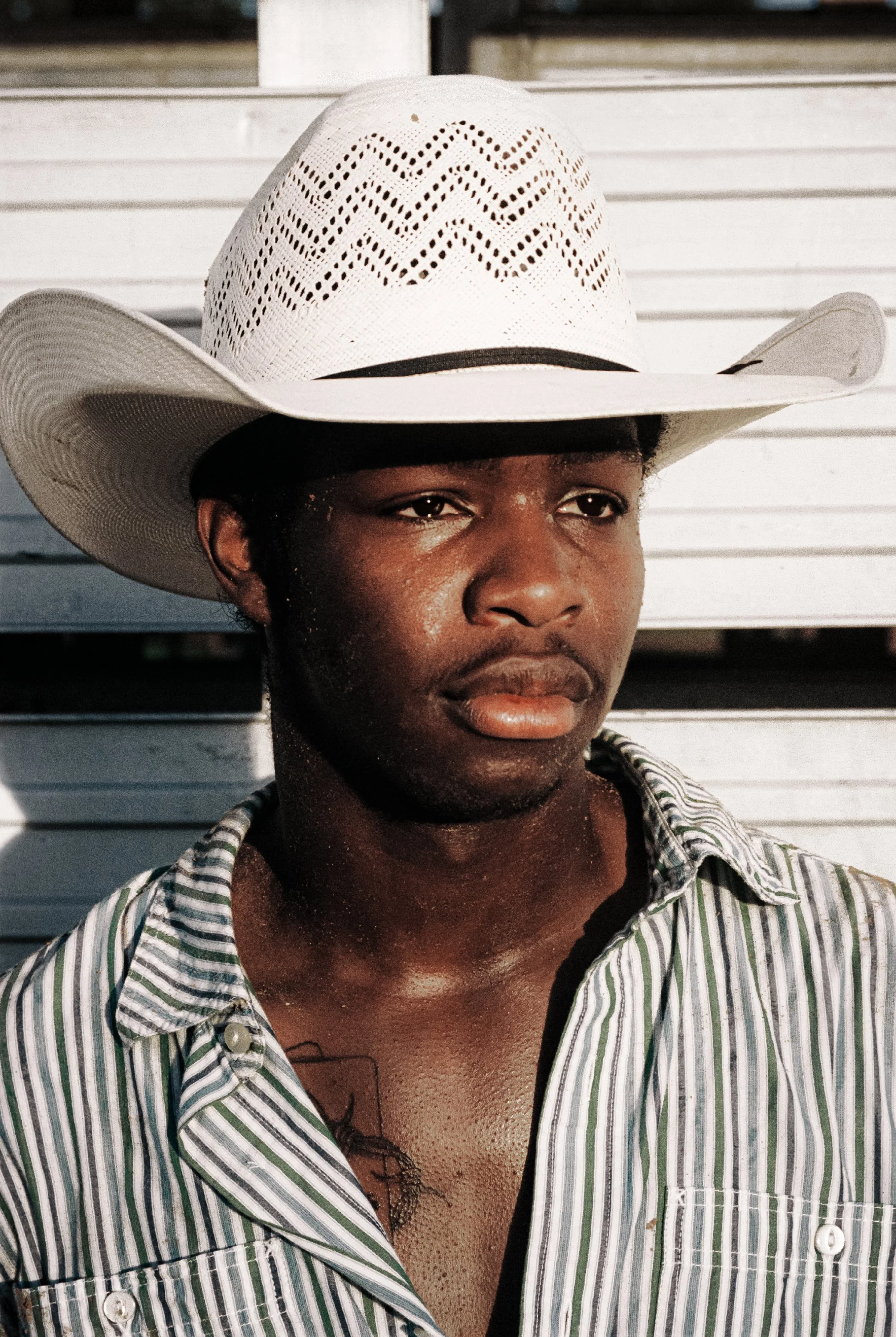

Interview Holly Wyche Photography Jorge MonederoSo my first question is about your use of religious imagery. You use it throughout the book to understand sexuality and to humanise people. For example, the reference to Saint Sebastian being full of arrows as akin to drug addicts pierced by heroin needles, is so compelling. Why do you think there is that relationship between sexuality and religious imagery, and does that have any relevance to your personal life?

My friend Roberta Marrero, who designed the cover of the book, always used to say that as Spaniards, we are all Catholic. Whether we want to be or not. And it happens that my sexual awakening was through a Catholic icon. I saw an image of Saint Michael when I was like four or five, and I can say that that was the first time in my life that I was horny. I think it was such a disturbing image, and I think the Catholic icons are so sexual, and that the artists who made these pieces did this intentionally. Religion is passion, and passion is sexy, and passion moves something in your body, in your mind, in your heart, that is so similar to sexuality. So, I think it's inevitable to use these icons. And I think that Catholic icons also have a very queer interpretation.

What drew me in about your writing was your specific description of trans experiences that seem inconsequential when living them, but deeply moving when you write about them. The example that came to mind was of hiding clothes in opaque bags, compressing all the air out of them and stashing them somewhere. How did you find it immortalising experiences like that?

Our lives are full of very literary situations. We have to grow, hiding in the corners while at the same time exposing ourselves in a world that is half hostile and half the opposite. I think our lives are so theatrical, and it's a waste of time not using all of these situations to write a novel, or to film something, or to create music. Our lives could be hard, but better, full of sensations. And these sensations are the tools of us creators. We are the best actresses and writers and everything else. Since we were little children.

The book feels very reactionary in the respect that it's told through protagonist’s response to all of these fantastic women she meets throughout her life, as a series of vignettes. What made you choose to write with this angle?

Because I remember the world of women like something magical, untouchable, and like a fairy world. I don't know why I rejected my male education. I don't know why. There's no explanation, but I rejected it. And every single thing that women in my life used to say was captivating. I will always be in a position of admiration of this world, even being one of these women now. I conserve this infatuation for a lot of the women of my life and the point of view of the novel, this celebration of womanhood, of sorority, is my real point of view. It’s half real and half tale, fiction and poetry like using Catholic icons. It’s inevitable that all my literature will be a celebration of womanhood and the point of view of a woman. It will be forever superior to other things.

"I don't exist as a writer without the books that I've read and the authors that inspired me, and there's always room in my work for others to pay tribute to other authors."

Also, class is a very major aspect of the book. The stories of Margarita and ‘The Wig’ are as much of class solidarity as they are ones of queer realization. I was wondering if you could tell me about how those two relate to you.

The point of view of women and the working-class are the two pillars of the novel. And I'm so tired that the majority of working-class tales that I read and see are of class tourism. I hate it. It's false and it's extreme. It's like a man doing a role as a trans woman. Politically, it’s a mistake, and artistically it's a failure. Not a single actor has done these roles well and for me it was very important I reflect my class experience. The neighbourhood, in the historical context of Spain in the early 80s, is a very concrete situation. Our world was a continuation of the world during Francoism and growing up in a neighbourhood like this marks your life and marks your life as a trans woman. There are no tools to understand who you are, not because working-class people are imbeciles but because they are tired. They are exhausted, and they have no time to talk because they are working every day from nine to nine. The family of the narrator is a loving family. They love their daughter a lot, but they don't understand her because they have no time. They are tired, they don't have the information, the education, to understand what the hell is going on with their daughter. And for me, it's one of the most important things in the novel. There’s this silence, this uncomfortable silence, which is inextricable from the class perspective.

The first line is a homage to Allen Ginsberg, and there are so many literary references throughout the book. How do you balance inspiration from these other places with your own writing?

Because I love literature, and I have been very happy reading other authors, and I pay tribute by writing with all of these people, of these works that inspire me. I don't exist as a writer without the books that I've read and the authors that inspired me, and there's always room in my work for others to pay tribute to other authors. I think part of my personality as a writer is mentioning others using the tools that other authors have given me.

I think that's almost an academic perspective!

Maybe! I think I use my academic background with a perspective of enthusiasm, and the tone, the rhythm, the inclusion of these inspirations in my work are like a celebration. Like using a colour in a painting, but instead you’re using mythology and medieval literature, or Allen Ginsberg. I think the secret is using that with love and as if you were playing with beautiful toys, and with beautiful colours and with beautiful things that you can use. The stories of literature, the stories of mythology are a room full of colour. And I tend to use it every time, and it's the way that my mind is built.

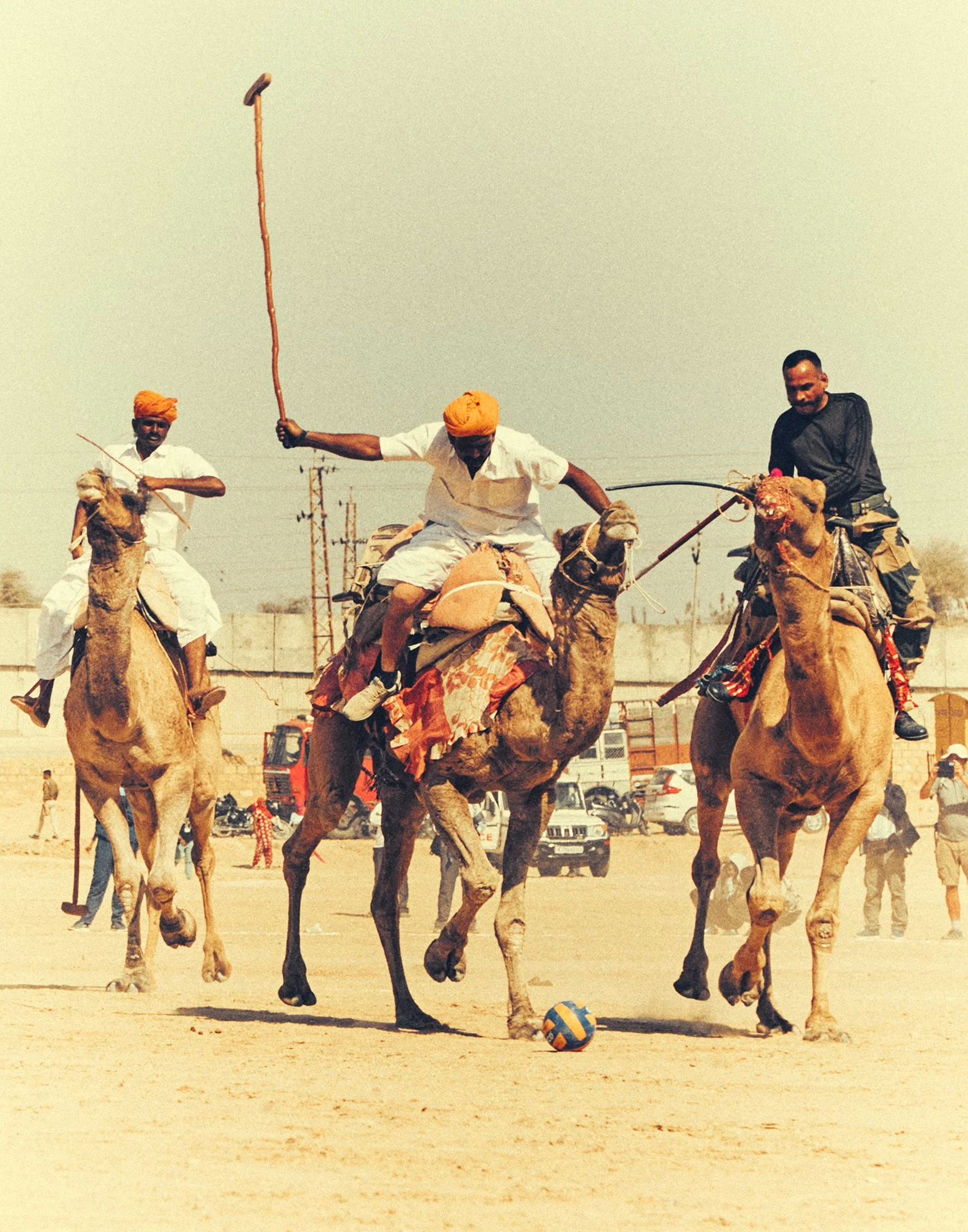

Also, you make these references with so much interdisciplinarity. Your music references for example, are so interesting. It’s amazing to see there’s a place for all those things in a single text, because a lot of the time they can feel very disparate and unconnected.

I think music and pop stars are the mythology of the present! So, I use Boy George or Morrissey the same way that I use Medusa or Achilles.

My final question is in regard to the film you're writing at the moment, which is an adaptation of My Dearest Senorita. I’m just wondering what the experience of adapting an old film is like compared to writing, especially with everything you just spoke about.

It's a difficult thing. I enjoy it a lot because the director of the film, Fernando Gonzalez Molina, and Los Javis, the producers, helped me a lot. They were very patient with me and very supportive. But at first it was hard, because it's another context, it's another terrain, and you have to adapt your literary mind to a very concrete scenario. All your literature is useless. You cannot write ‘this person is sad’. No, you have to show that this person is sad. And you can write a lot of motivations, a lot of insights about the character, but in frame, you have to show it. It's difficult, but I’ve learnt a lot. It is absolutely incredible. I am very looking forward to it!

“Religion is passion, and passion is sexy, and passion moves something in your body, in your mind, in your heart, that is so similar to sexuality. So, I think it's inevitable to use these icons. And I think that Catholic icons also have a very queer interpretation.”

About Alana

To find out more about Alana’s work, follow her on Instagram

Special Thanks to Jorge Garriz, Romancero Books and Brenda Otero