The eerie Queerness of Jenkin van Zyl

In Lost Property (2025) video artist Jenkin van Zyl invites viewers into a looping bureaucratic dreamscape where the lost isn’t luggage—it’s selfhood. Known for his cinematic hallucinations, van Zyl blurs the lines between fantasy and surveillance, rendering bureaucratic absurdity as a theatre of horror. In our exclusive interview, we delve into the making of Lost Property, the queerness of cannibalism, the politics of overconsumption and how dressing up becomes a form of resistance to our bleak times.

Interview Giulia Piceni Photography Christian Trippe Photo Assistant Ezra EvansA couple of days ago, I watched Lost Property (2025), your most recent work on view at ARoS. In your words, what is Lost Property ultimately about?

Lost Property follows three characters navigating a bureaucratic simulation that claims to offer recovery for what has been lost. Each of them is propelled through a personal loop, encountering their doppelgänger—versions of themselves left behind in the Lost Property Bureau. Though they are drawn back to this eerie building, the search is not for misplaced keys or wallets, despite the clutter of ordinary lost items. Instead, their pursuit is something far less tangible: identities. The Bureau operates both as the setting and as the mechanism of the loop that forms the structural core of the film. I’ve always been fascinated by how video art is experienced in galleries—looping without end, with no clear beginning or conclusion. This structure becomes a way to explore time as something resistant to linear interpretation and allows for the development of a sympathy for characters caught in the cycle of endlessly performing versions of themselves.

When I first encountered your work, I immediately thought about the hallucinatory worlds of Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle, as well as the queerness of Leigh Bowery. Which are the icons, the mentors, the subcultural figures that have impacted your artistic language the most?

I've always been drawn to preposterous, fantastical and queer figures who explore both the potential and the burden of the body. That anarchic, irreverent form of queerness found in Bowery’s work has always held a strong appeal, so it’s been especially compelling to see it recently curated so thoughtfully by Fiontan Moran in a major institution such as the Tate Modern. As a teenager, I was captivated by filmmakers like Alejandro Jodorowsky, John Waters and David Lynch—those formative figures who serve as early entry points into ideas of otherness. I was also deeply influenced by the work of Jan Švankmajer, the Czech animator, particularly to the itchy textures of his sound design.

“I’ve always been fascinated by how video art is experienced in galleries. Looping without end, with no clear beginning or conclusion.”

You tend to release your works with a significant timing between. How did that journey unfold specifically for Lost Property?

Filmmaking is inherently collaborative in how it brings together fantasists to create a world together. For this project, I began with the unstable concept of a lost property department. Early on, we visited London Transport’s lost property offices to observe the absurdity of the objects and the quietly surreal systems that process them—though their bureau ran far more smoothly than ours ever could! The work evolved from my ongoing interest in repetition, doubling, and the performances demanded by bureaucratic spaces. I wanted the piece to mirror the unsettled tone of our current cultural moment, embodied in the figure of the doppelgänger: a glitchy double that troubles ideas of authenticity, reenactment, and mistrust amid faltering institutions. The project took shape through location scouting, casting, and costume design, all of which fed back into the scripting process. Unlike earlier films of mine that leaned more heavily on improvisation, this one required a greater degree of narrative continuity—blending task-based improvisation with tightly structured sequences.

Despite the circularity and the looping structure, one can spot three interwoven cycles, each centred on a distinct character. How did you go about conceiving these three characters?

The cast responded intuitively to their characters. One narrative loop involves a meeting with a doppelgänger that devolves into auto-consumption, with one character transmogrifying into cake and ultimately being devoured by the other. This role is played by Alex Margo Arden, my best friend and long-time collaborator, for whom I often write roles. Her counterpart is Elly Clarke, a performer whose research explores the burden of the body but also has a drag persona Sergina that is open source and can be played out by others. Cannibalism is a recurring theme for me, especially in how desire pushes into extremes. In this case, the consumption is both literal and metaphorical: a scene about intimacy, destruction, and the impossibility of remaining whole. Another loop features Lewis Walker, a former gymnast and artist, in a loop they choreographed of themselves with Alex Thirkle. The third loop centers on Jaya Twill and her double Zuleika Lavender, whose narrative takes a meta-fictional turn as she repeatedly auditions for a shifting role in the film.

“When developing a project, I tend to begin with a structure or setting that feels unstable enough to accommodate contradiction within its narrative framework.”

At ARoS, Lost Property is presented within a lavender-hued set. How does this scenographic environment shape the viewer’s experience of your work?

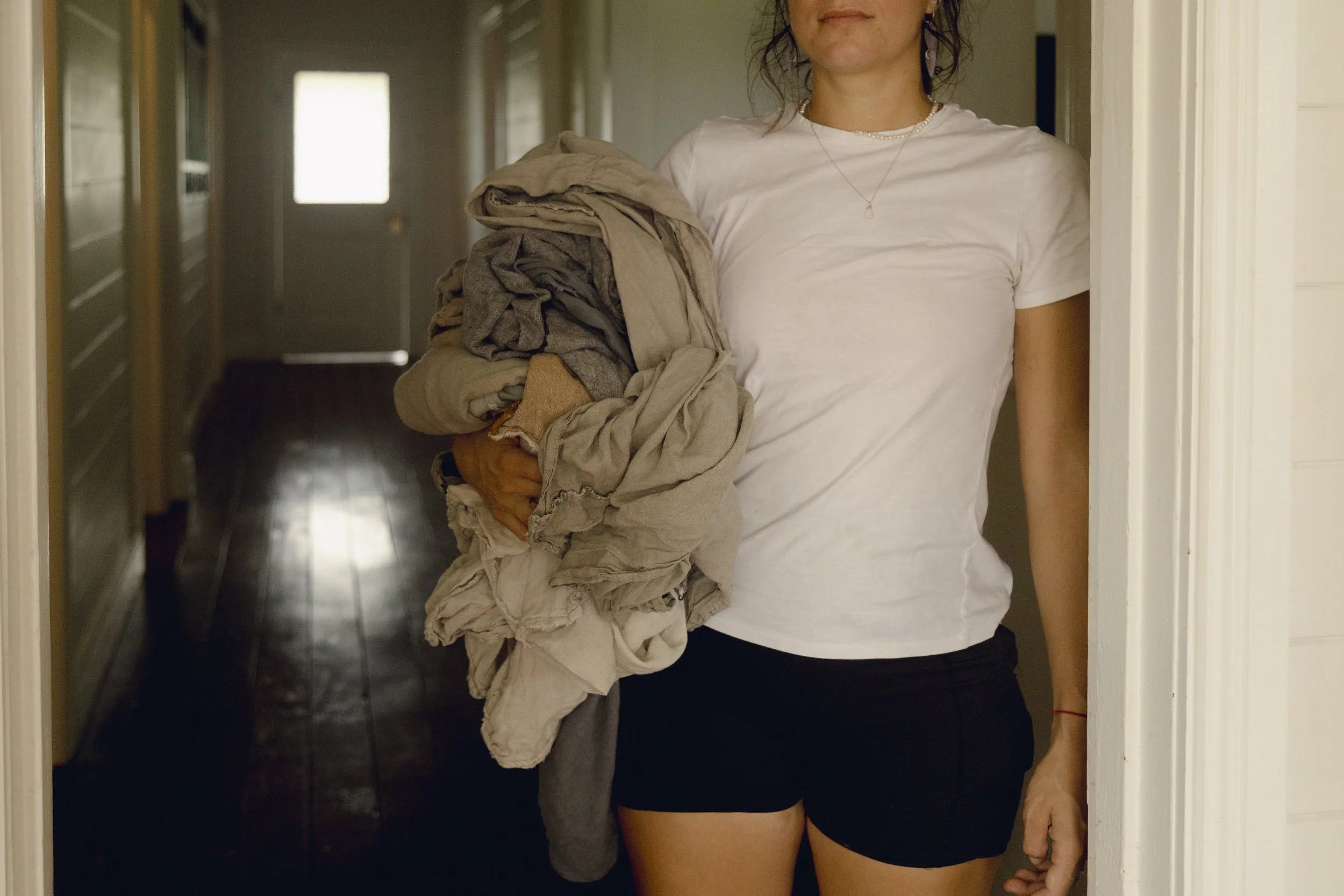

I’m aware of the sculptural quality of the spaces where my work is shown—spaces that function like theatres or cinemas. In previous projects, I’ve designed environments that shape or disrupt the viewer’s physical relationship to the screen, such as shared beds for audiences or reconstructed aeroplanes as part of the context. For this project, the spatial approach is more explicitly theatrical. The scenography relies on drapery, creating an eerie, ghost-like atmosphere. Large backdrops reproduce the Bulgarian street set on semi-translucent gauze. Passing through them, viewers reach a vast spiralling lavender curtain, the nucleus—or brain—of the bureau. Inside, compressed bales of discarded clothing form staggered seating, referencing both the volume of waste processed and the overwhelming surplus of potential identities and disposability.

This setup strongly connects to themes of overconsumption and performativity from your earlier work, now within an institutional setting. The film opens with creatures both observing and being observed. What draws you to the recurring motif of observation and scrutiny in your work?

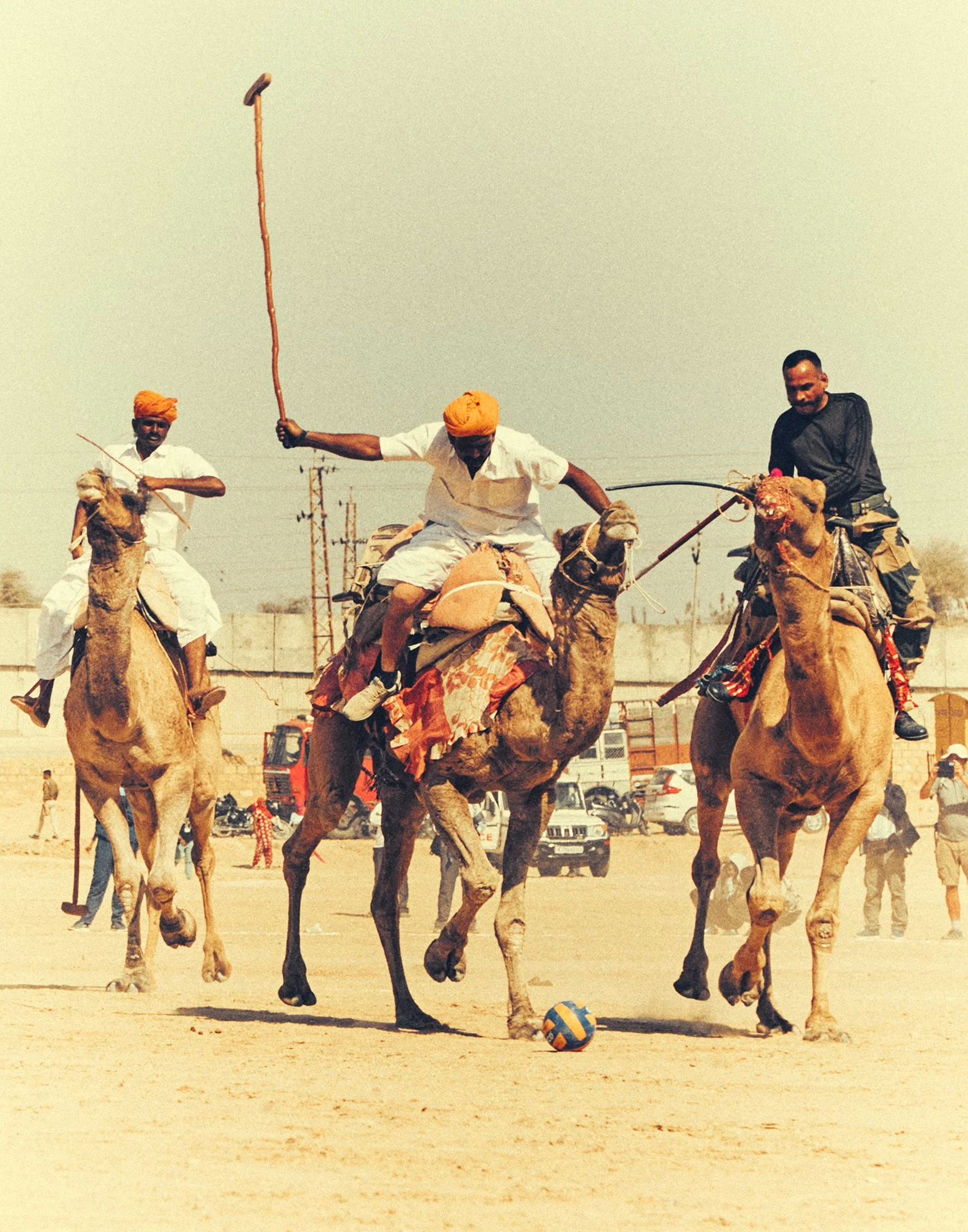

My previous film, Surrender, drew on 1920s dance marathons to explore performance and proto-reality TV, but at the core of my work is the theme of escape: how countercultural spaces form new meanings yet become shaped by the systems they resist. I’m particularly interested in how omnipresent surveillance affects liberation, autonomy, fantasy and desire. In Lost Property, the bureau staff—composed by an extravagant, absurd group of queens—parody bureaucracy by hyper-monitoring characters’ seemingly autonomous choices, creating a layered dynamic of observing and being observed that highlights how surveillance shapes identity.

I would say that this sense of surveillance is deepened even more throughout the film, especially in the scenes showing the outside world—these abandoned movie sets bathed in a very cold light. Would you say that reflects your view of contemporary society as a space governed by control and absence?

The Bureau’s hiding behind a fake London street set in Bulgaria is deliberate—surveillance today isn’t always obvious control; it’s often seductive, immersive, and aesthetic. Simulations become the system, with platforms watching, archiving, and shaping how we perform ourselves. The film mirrors this, showing the “real” street as eerie and empty, while the artificial set hosts more authentic performances. It reflects our mediated lives, where chaotic spectacle mixes horrors with banal content—like TikTok’s endless, jarring stream of pleas, tutorials and exploitation. I wanted the film to capture that confusion, where authenticity and performance blur through layers of simulation, but also carry a dark humour that hints at how these systems might be unravelled, despite their exhausting grip.

“I dress like a dark twist on a Russian Ballets Russe dancer, with devil tails and horns.”

Fashion plays a key role in your practice. How did you handle the costume choice that has been done for Lost Property?

The bureau staff wear almost fetishistic versions of office uniforms, featuring flashes of latex and gimp masks, combined with a veneer of being very buttoned-up and suited. The three protagonists, in contrast, appear as unhuman, ghoulish, monstrous figures. Their base costume consists of body stockings and tights that blend seamlessly with their skin. When outside in the narrative, they dress in human disguises inspired by lost property disguise catalogues. All these clothes were sourced from luggage auctions and lost and found sales, places where uncollected luggage filled with discarded, often unwashed clothing is sold. In encounters with their doubles, the characters wear flamboyant costumes—baby doll styles that are highly effeminate, featuring transluscent nightwear, frills and bonnets.

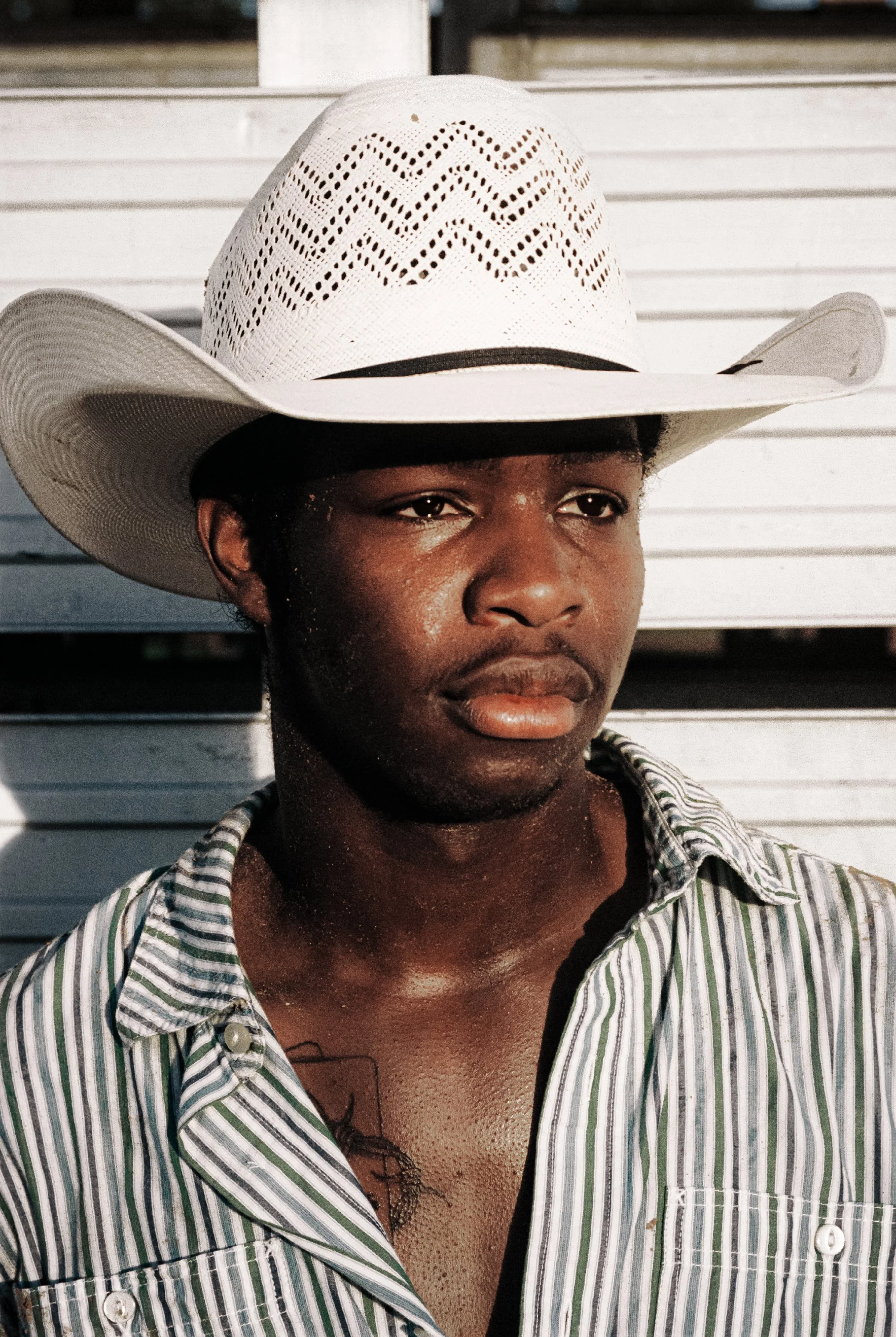

And what about your own relationship with fashion, especially relating to the shoot you’ve just done for this interview?

I love theatre costumes and have tonnes of pieces sourced from costume clearances—everything from Elizabethan doublets to cheetah print unitards and armour. I dress like a deranged Russian Ballets Russe performer, with devil tails and horns. My style overlaps with the film costumes, but it’s its own kind of world-building. It’s not romanticised—just a way to make life less boring. Dressing up is a coping mechanism in a bleak world. I like mixing the weight of theatrical wool with the provocation of garters and jock straps—combining drag, drama, and heat-responsive pragmatism in the same outfit.

The exhibition now at ARoS is a big step, a big milestone in your career. How do you envision your practice evolving from here?

I am currently working on another film project, which I consider a kind of equivalent art film. For this one, I intend to incorporate more scripting and dialogue, as my previous works have rarely given the characters a direct voice. Typically, the soundscape and sound design function as substitutes for speech, amplifying the characters’ actions and thoughts. However, with this new project, I want to introduce actual dialogue and structured scripting. Following that, I plan to undertake a very different project—one without masks or prosthetics—shot in the style of an immersive reality show, where the participants live together throughout the filming process. Afterwards, I aim to create something closer to a traditional narrative feature film!