Icons: Man Ray

A retrospective of Man Ray’s approach to exploring advance, contradiction, and how his ethos affected both fashion photography and surrealism.

Text Tom Wyche Self Portrait With Camera, 1932

“There is no progress in art any more than there is progress in making love. There are simply different ways of doing it.”

Laboratory of the Future, 1935

Sleeping Woman, 1929

Ray spent his artistic career exploring dramatic new movements and approaches to photography that not only established fashion photography as a more respected field, but simultaneously challenged preconceived notions of photography through his contribution to the surrealist movement. While he’s celebrated commonly for his obtuse physical work, such as the piece “Object to Be Destroyed”, what I find most compelling is with Ray’s idea of progress.

Indestructible object (or object to be destroyed), 1923

Within his initial exploration into photography in the early 1920’s, Ray’s multiple trademark techniques were ironically the furthest thing from modern. His eponymous Rayographs use a method of capturing light that predates even the existence of photography as a medium. In his 1922 discovery, Ray dropped an unexposed sheet of photography paper into the developer while working in the darkroom.

“Regretting the waste of paper, I mechanically placed a small glass funnel, the graduate and the thermometer in the tray on the wetted paper. I turned on the light, before my eyes an image began to form. [...] They looked startlingly new and mysterious”

Despite calling this a progressive method, he’d essentially stumbled onto a proto-photographic method known as a photogram. This process is as simple as putting objects directly on light sensitive paper, and after exposing it to light, one’s left with a shadow-y outline. This has been a defined practice since the 1840’s, predating Man Ray’s discovery by over 80 years. Of course the portmanteau of the name “Rayograph” shows this is a tongue in cheek assertion, and that Ray was firmly aware of these historical methods.

“I have finally freed myself from the sticky medium of paint, and am working directly with light itself.”

Untitled, 1922

Untitled, 1926

But this in and of itself is notable. Ray’s exploration of progress through a return to historical methods is a repeated interest of his, having also experimented with Solarisation, a process dating back to the 1840’s where one exposes a print to a flash of light during its’ development, causing part of the image to develop as a negative and part as a positive. Ray (alongside Lee Miller) also described himself as the discoverer of this method, to a degree where even institutions like the Tate attribute the method to him despite its history, being used aesthetically all this time.

The point of these examples isn’t to suggest Man Ray is unoriginal in any regard. I think instead it shows his remarkable way of exploring his interest in possibility and progress where, instead of jumping on gimmicks of the time, revitalising primitive methods in an exciting way and presenting them as new. While one can try to draw some greater artistic meaning from this contradiction, Ray himself is known and is quoted as being contradictory solely for the sake of it.

“I like contradictions. We have never attained the infinite variety and contradictions that exist in nature. Tomorrow I shall contradict myself. That is the one way I have of asserting my liberty, the real liberty one does not find as a member of society.”

This idea of contradiction seems so integral to understanding Man Ray and comes up time and time again in his career: He toyed with new methods and worked outside of the bounds of established artistic methods, but simultaneously believed progress wasn’t a real concept in art. He was a major part and influence on both the Surrealism and Dada movements but refused to be ascribed to either. Even his work, regardless of the era, felt like it had this disconnect baked into it. An article from the LA Times in 1978 describes it perfectly, stating “whatever he created somehow appeared to be brand new and familiar at the same time.”

Glass Tears, 1932

The Kiss, 1922

Woman with long hair, 1929

This is particularly true of his movement into surrealism. In the mid 1920’s, Ray moved to Paris and continued his experimental photography, colliding with the emerging surrealism movement that fit this contradictory ethos perfectly. Admittedly his most commercially successful work during this period was his fashion and portrait photography, with his presence becoming as ubiquitous as to create “a virtually complete photographic record of the celebrities of Parisian cultural life”, being featured in Vogue and other notable magazines. Ray’s lasting work however was his far more experimental pieces, produced in the same time adjacent to his more palatable work.

Gertrude Stein, 1920-1929

Bronislava Nijinska, 1922

Erotique Voilée, 1933

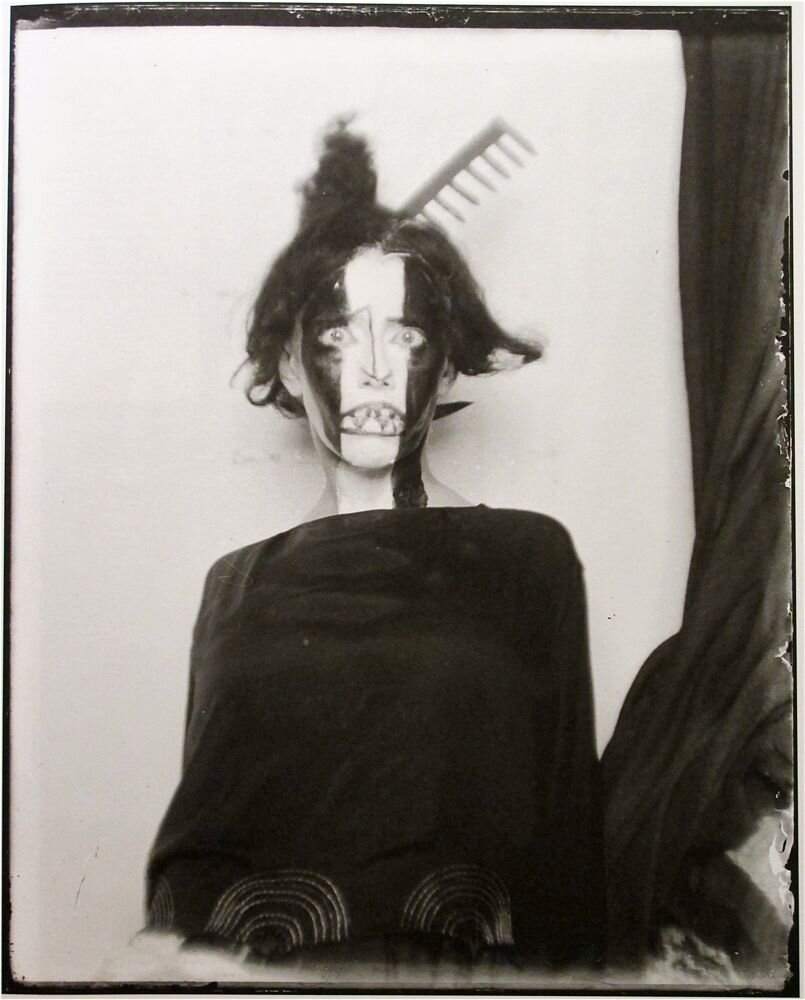

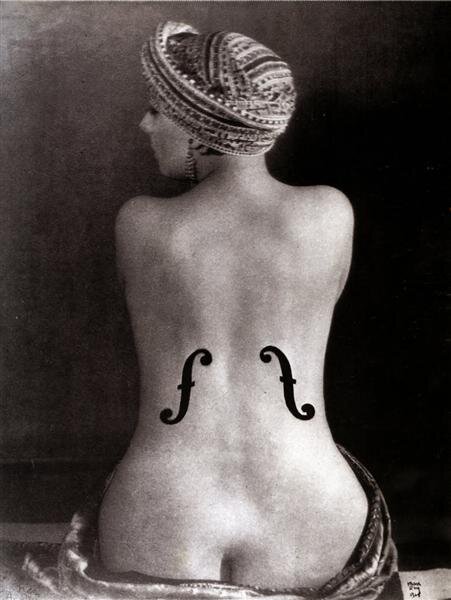

It’s fairly easy to announce these as two separate lines of his work, but there is an extremely notable overlap in both that lets one see Ray’s ascent into surrealism. The fashion photography Ray undertook gave him both the connections and the practice to lean into and play with Surrealism in the late 1920’s, exploring the Freudian origins of the movement. He is described as having notes of “disturbing Freudian strangeness” within this era of fashion photography, portraying nudity and a fascination with mannequins that was undoubtedly unnerving. Ray’s independent, fully surrealist work strikes a similar tone, featuring a combination of prop-based work and portraiture that contorted the human figure in a way that produces an almost fascinating discomfort.

Anatomies, 1929

Le Violon d'Ingres, 1924

Through all of this however, what has become apparent is that Ray views artistic discovery and progress not as a linear series of events, where exploration leads chronologically from one field to another, or from one discipline/movement into the discipline that naturally progresses from it. Instead, as Ray himself has said, he simply explores the different ways of realising the ideas that came into his head, regardless of the direction of the movement they relate to. While this may sound like a simplification of his work, I think instead this is what allows Ray’s work to feel so enigmatic and contradictory. Pieces such as anatomies, or his untitled Rayographs are so clearly a product of the time’s movements of Surrealism and Dada, yet exist above them, not following trends but engaging with its own thought patterns. Once again, Ray’s work feels “brand new and familiar at the same time”.

Untitled (Self-Portrait of Man Ray), 1933

About Man Ray

Ray was born on August 27, 1890 as Emmanuel Radnitzky, going on to study photography at the Ferrer school, New Jersey.

He received the Royal Photographic Society’s Progress Medal, alongside an honorary fellowship, posthumously in 1974.

Find out more about his life and current exhibitions at the Man Ray Trust